1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, will releasing the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles to be reviewed. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

It would seem fitting that in 2014, the fortieth anniversary of Dungeons & Dragons—the game that would inaugurate roleplaying as a social pastime, that would inaugurate roleplaying and gaming as an industry, and that would influence the multi-million dollar computer games industry—that the first review in this series be of the original Dungeons & Dragons boxed set. Sadly I do not have a copy of this in my collection, though the year is only half done and there is time for me to obtain such an item yet. Thus the inaugural entry in the anniversary series will be of a grand, classic board game—Kingmaker!

Kingmaker is a simulation of the Wars of the Roses, the period of sporadic Civil War in England between 1450 and 1490 that saw the two rival branches of the Royal House of Plantagenet—the houses of Lancaster and York—and their supporters vie for dominance, and ultimately, the English crown. Each player will take control of one the factions of Noble families aiming to use their influence and military forces to manoeuvre a claimant to the throne and into power whilst preventing rival factions from doing the same. Thus the players are not the claimants and heirs to the throne of England, but potential powers behind the throne, each the very ‘kingmaker’ of the game’s title, itself taken from the nickname for Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, the most powerful noble of his age.

The game is designed for two to seven players—though as many as twelve could play—and takes anywhere from two to six hours to play. The ultimate aim is for one faction to control and have crowned a claimant to the throne after all of the others have died or been killed.

|

| The Kingmaker board; a fabulous jumble of irregular geography. |

Kingmaker is played out over a map of the Wales and England of the 15th Century—with the port of Calais to the southeast on the corner of northern France across the English Channel—that is marked with the two countries’ various castles, royal castles, towns, fortified towns, ports, and major geographical features. Broken down into irregularly spaced and sized squares, the map is a messy jumble that is often difficult to navigate or find anything on.

The heirs over which the player factions will feud over are comprised of seven Royal Pieces. The Lancastrians consist of Henry of Lancaster—actually Henry IV of England at the start of the game, plus his wife, Margaret of Anjou, and his son, Edward of Lancaster, the Prince of Wales. Another Lancastrian heir is the noble, Beaufort, but his claim can only be pressed once the other Lancastrian heirs have died. The Yorkists consist of Richard, Duke of York, and his three sons, Edward, Earl of March, George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

|

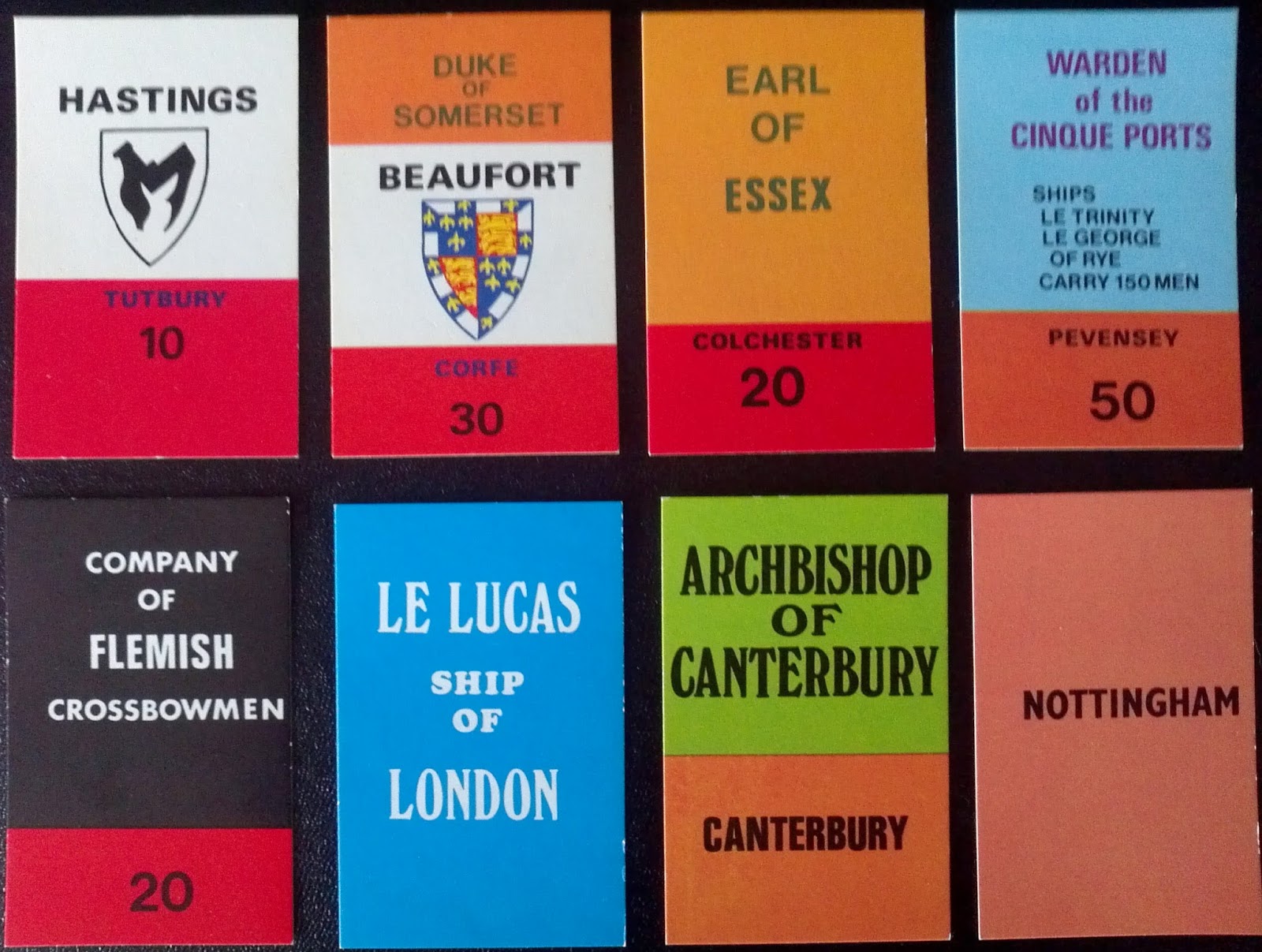

| Crown Pack cards, from left to right (upper row): a Noble, a Noble with a Title, a Title, an Office; (lower row) a Mercenary Unit, a ship, an ecclesiastical office, and a town |

Each of the nobles that form a player’s faction is represented by a card and a counter, both marked with the noble’s coat of arms. A noble’s card also indicates which castles he holds and the number of men-at-arms he commands. Most nobles are knights and barons, but some also have a title. For example, Percy is the Earl of Northumberland, owns the castles of Alnwick and Cockermouth, and commands one hundred men-at-arms, whereas Audley owns Tickhill castle and commands just ten men-at-arms.

Titles are important—and others may be awarded throughout the game, like the Earl of Worcester or Duke of Exeter—because they also make a noble eligible to be appointed to an office, for example, Marshal of England, Warden of the Cinque Ports, or Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Each of these offices grants the holder further men-at-arms and in most cases, extra benefits. For example, the holder of the Warden of the Northern Marches gains fifty men-at-arms, plus a further one hundred troops when he is north of the River Tees and the towns of Bamburgh and Berwick, while the Admiral of England also gains fifty men-at-arms, two ships, and the towns of Southampton and Lynn. With most offices come certain responsibilities. For example, the Warden of the Northern Marches might find himself sent to Berwick if the Scots launch a raid and the Marshal of England to Bodmin to put down a peasants’ revolt. A noble can also hold ecclesiastical office, for example, Archbishop of Canterbury or Bishop of Norwich. They each grant control of a town with a cathedral, but more importantly, they enable a faction to hold a coronation and crown an heir—an Archbishop can do this as can a pair of Bishops.

At the start of the game, the seven Royal Pieces are placed in their starting locations and the game’s two decks—the Crown Pack and the Event Pack are shuffled. From the Crown Pack each player is dealt a certain number of cards, the number dependent on the number of players. From these cards, a player sorts his nobles and assigns them titles, offices, and ecclesiastic positions, plus mercenary units (for example, Company of Flemish Crossbowmen or Company of Saxons), towns (Shrewsbury or Ipswich), and ships (Le Rose, Ship of Plymouth or Le Michael, Ship of Bristol). Any titles and offices that cannot be assigned go into second deck known as Chancery. They can only be reassigned when the faction controlling the sole crown king can summon Parliament during play.

|

| Kingmaker set up for four players. |

Once everyone has formed their faction and placed their nobles’ counters on the board, play begins. On his turn a player draws from the Event Pack, moves his pieces and engages in any battles, and then draws from Crown Pack. The card drawn from the Event Pack might grant a noble a Free Move or the faction a Writ of Summons to Parliament, which the player can keep until used. Other Event Cards are potentially more interesting. Each of these is divided into an upper and a lower half. The upper half presents an event, the lower half the victory odds used in battle. Events can include a French Raid, an Embassy, or a Plague. The first of these sends the Warden of the Cinque Ports to Pevensy with one ship—though similar events will send other Office holders and nobles to various places. The second sends the King to a particular location to receive the ambassador, whilst the third causes the death of anyone in the named location, for example, Lincoln or Newark.

|

| Cards from the Event Pack. |

Movement is simple—all units can move five spaces per turn. Sea movement is greater because the squares are larger and it possible to transport troops by sea. Battles—and there can only be land battles—are handled not by rolling dice, there being no dice in the game, but by odds. When two factions engage in battle, each side totals the men-at-arms it has at its command—derived from titles, offices, mercenaries, and so on, and the ratio between the two sides determined. An Event Card is drawn and the ratio on the card compared with the ratio of forces involved in the battle. If the ratio of the forces is greater than that on the card, the lesser side has been defeated, its nobles killed and stripped of their titles and offices. Both titles and offices go into the Chancery deck, while the nobles go onto the bottom of the Crown Pack, where their heirs will be drawn later in the game to declare for one faction or another.

Although battles come down to which side is larger, they are all the more interesting for two factors. The first is that bad weather can delay an attack, enabling one side to escape from the other. The other is that each battle result is accompanied by one or more names of nobles. If they are part of either side in the battle, then whatever the outcome, they are also killed.

For example, an Event Card has been drawn that brings down the Plague! upon London, resulting in the death of Henry of Lancaster. In response, Neville, the Earl of Warwick (50) and Archbishop of York in command of a Company of Burgundian Crossbowmen (30) is racing north to capture the leading Yorkist heir, Richard, Duke of York. His aim is to crown Richard and proclaim him king. He has a total force of 80 troops.

To prevent Neville from gaining an important lead, two other nobles move to counter him. Clifford (10), the Earl of Westmoreland (40), in command of a Company of Scots Archers (20), Stafford, the Duke of Buckingham (30) and Warden of the Cinque Ports (50) together have a total force of 150 troops.

|

| Neville versus Stafford and Clifford with the Battle Card that determines the results between them. |

Under certain circumstances, Parliament can be called. Primarily this can be done with a Writ of Summons to Parliament by whichever faction is control of the sole crowned king. If one of the nobles in a faction is the Chancellor of England, then he may also summon Parliament under certain circumstances. Doing so enables the summoning faction to reassign many of the titles and offices that have been lost to Chancery through previous events. It is a means for the summoning faction to bolster its standing.

The last action a player does on his turn is draw from the Crown Pack. This may give him a new noble, ship, town, or company of mercenaries to add to his faction. It may also give him a new title or office—one that has not entered play yet and thus is not in Chancery. The player may add this to his faction immediately if he can, but he can also choose to keep it secret. In this way, the true strength of a player’s faction can be kept hidden until revealed at the right moment—perhaps a noble declaring for one faction or another, a faction making a propitious hiring of a company of mercenaries, and so on.

This then is the core of the game. Once past the set-up, Kingmaker proceeds with most factions trying to build their power and bringing their nobles together. This will be hampered by events drawn from the Event Pack. Too often a faction will find its forces riven by the effects of events. This occurs to nobles, to office holders, and to the King. So the noble Douglas will be forced to return to Douglas in the Isle of Man due to piracy; a peasant revolt will oblige the Duke of Exeter to return to Exeter, the Chancellor of Duchy of Cornwall to Plymouth, and the Marshal of England to Bodmin; and the King must go to Preston to receive an Embassy from the King of Scots, and whichever faction holds the King has to decide whether or not to accompany him. This has a number of effects. First, it splits the forces and nobles of factions apart and weakens them. Second, it makes these nobles vulnerable to attack by factions which would otherwise be too weak to attack the combined faction that the nobles were split from. Third, it slows the game down as factions try again and again to bring their nobles together. Fourth, it adds a sense of verisimilitude to the game.

The aim of this power build-up is two-fold. First, it gives a faction sufficient combat strength with which to defend itself. Second, it gives a faction sufficient combat strength to capture claimants. Initially, there are one or two ways in which a claimant can be captured. One of these is for a noble to hold an office which grants him the town where the claimant is. For example, Constable of the Tower of London grants a noble the deeds to London, so is a powerful office at the start of the game because that is where the King, Henry of Lancaster starts the game. Similarly, the office of Marshal of England grants the holder the town of Harlech where Edward of March, a Yorkist claimant is found. In other cases, simply receiving the town, for example, that of Coventry where Edward of Lancaster begins the game, will grant a faction access to a claimant. A faction can only hold claimants from one house, not both, and a faction is free to do with the claimants with what it wants—it can exchange them, give them to other factions, or simply have them murdered.

This highlights the role of the Royal Pieces in the game. They are a resource, a possible bargaining chip, and a means to an end. It is necessary to have one in order to win the game, but if a claimant stands in a faction’s way, then he is disposable, and similarly, if a faction stands to gain by giving a claimant to a rival faction, he is also disposable. In all three roles, the use of the Royal Pieces becomes part of another aspect of Kingmaker—diplomacy. The players are free to engage in alliances and deals throughout the game. Doing so is one means for weaker factions to harass and even destroy stronger factions by working together, and of course, breaking a deal and betraying your allies is perfectly in-keeping with both the game and the Wars of the Roses.

Physically, Kingmaker is very nicely presented for a game published in 1974. The map is large and colourful and the pieces are equally colourful. In most cases, they are easy to identify, but some are identical bar their different colours. The game’s cards feel a bit soft and flabby, but they are large and easy to read. What was surprising on returning to the game was that the rulebook, though done in black and white without any illustrations, was well written. Despite it being over thirty pages long, it is easy to read, the rules come with plenty of examples, and it ends with a lengthy discussion of how the game should be played.

One issue with the game is when it runs into a stalemate. Typically, the factions have built themselves up as powerful as possible and retreat to their power bases, regions where they have extra troops because of an office. For example, the holder of the Chamberlain of the County Palatine of Chester has two hundred extra troops whilst he is in Wales. When this happens, it will take an Event Card to drive them from their refuge and leave them vulnerable to attack by a rival faction. In the meantime, not a lot may happen… Which given the potential playing time of the game, it can make the game a little dull. Another issue is that combat is simplified by modern standards, with little chance of a smaller force surviving an attack. The best it can hope for is bad weather and the chance to escape—there is no chance of it snatching victory from the jaws of defeat.

Originally published in 1974, Kingmaker would receive the Charles S. Roberts Award for Best Professional Game of 1975—these awards being given annually for excellence in the historical wargaming—and be republished in 1975 as a second edition by Avalon Hill. A later Expansion would add new Event Cards, but the second edition added a more complex means for handling Parliament, bringing voting into the process—a discussion of which can be seen here—as well as adding Ireland and parts of Europe to the game. It was certainly popular enough to be the subject of numerous articles in The General, Avalon Hill’s house magazine and it was turned into a computer game by Avalon Hill in 1994. Much like the earlier Diplomacy—a game that itself is sixty years old in 2014—Kingmaker has the capacity for player negotiation away from the board and thus could be played over time by post as a PBM or ‘Play-By-Mail’ game rather than face-to-face with everyone sat round the table. It has though, been out of print for several years, although the Wars of the Roses have been revisited more recently in game like Columbia Games’ Richard III: Wars of the Roses and Z-Man Games’ Wars of the Roses: Lancaster vs. York. Further, its influence can be seen in Games Workshop’s Warrior Knights and more obviously in Fantasy Flight Games’ A Game of Thrones—but then that is a given since the George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels are themselves inspired by the Wars of the Roses.

Revisiting Kingmaker satisfies a sense of nostalgia for the game and the chance to revisit it as an adult rather than the teenager I was when I was first playing it. When I was originally played, it was out of an enjoyment of the game’s sense of history. That history—even though that history is ahistorical rather than absolutely faithful—is still much present in coming back to the game. As is its pageantry and its theme, all of which is very well handled in the game. As a game design though, Kingmaker does show its age, it is perhaps too slow in places and too basic in others, but the pageantry, the theme, and the history more than make up for the deficiencies in the design.

Kingmaker is rightfully regarded as a classic boardgame and there can be no doubt about that. The question is, forty years on from its original release, is it time for a redesign and a release?

No comments:

Post a Comment