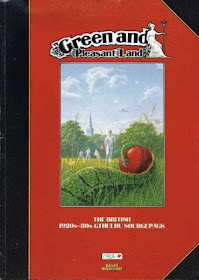

With the sixth entry in the Call of Cthulhu Classics series, we come to the fifth and last release for Call of Cthulhu from Games Workshop, following on from Trail of a Loathsome Slime, Nightmare in Norway, The Vanishing Conjurer & The Statue of the Sorcerer, and of course, the highly regarded hardback edition of Call of Cthulhu, Third Edition. That release is Green and Pleasant Land: The British 1920s-30s Cthulhu Source Pack. Published in 1987, it was not quite the first supplement to explore the United Kingdom during the RPG’s default period of the Roaring Twenties—that honour would arguably go to the campaign, Masks of Nyarlathotep, with its own London chapter, published in 1984. It was though, the first to look at this ‘sceptr’d isle’ in any real detail and arguably also the first to look at the 1930s for Call of Cthulhu as well. Of course, it would later be superseded by Chaosium, Inc.’s own The London Guidebook in 1996, and then by several supplements—of varying quality—from Cubicle Seven Entertainment for its Cthulhu Britannica line culminating the Cthulhu Britannica: London Box Set. Along the way, the 2008 Miskatonic University Library Association Monograph, Kingdom of the Blind: A Guide to the United Kingdom in the 1920s and 1930s can be seen as a missed opportunity, whilst the Masks of Nyarlathotep Companion with its extensive London chapter has yet to appear as of late 2016.

Green and Pleasant Land is an eighty-page, over-sized book roughly divided into two halves, one devoted to background information and the other to a trio of scenarios. Ending the supplement is Brian Lumley’s short story, ‘The Running Man’. This is a decent piece that concerns the disastrous attempt by some amateur ghost hunters to investigate a haunted house and nicely sets the scene for the scenarios that precede it. The background half of Green and Pleasant Land consists of a series of short sections that vary in length from a single page or less to as many as five. They cover mundane subjects such as British social life, communication, entertainment, crime & punishment, public health, and travel—aviation, the inland waterways, motoring, railways, and sea travel. There is a mundane and a Fortean timeline as well as sections devoted to archaeology, follies, the occult, and the Mythos. After listing various notable figures from the period—including various fictional ones such as Hercule Poirot, Jane Marple, and James ‘Biggles’ Bigglesworth—it introduces various new Occupations specific to Great Britain. These are Gentlemen, Players, Butlers, Valets, Sleuths, and Sportsmen, all nicely detailed with more background and discussions of how they should be played than is the norm for Call of Cthulhu. There is also the first mention of rules for prior experience for investigators who fought in the Great War. These rules are not particularly detailed, but they are a good start (and were the basis for an expanded article on the same subject in the Masks of Nyarlathotep Companion). Now of these new Occupations, most consist Occupations for Middle and Upper Class Investigators, so from the outset the tone of the supplement is ‘What ho!’, more Jeeves and Wooster Pulp tone than anything approaching Purist.

Where Green and Pleasant Land begins to get interesting is in its exploration of the outré. So there are solid sections on the occult—witchcraft and Aleister Crowley in particular, as well as a discussion of Harry Price and the Society of Psychical Research. The relatively lengthy discussion of the archaeology of the period, which covers everything from British barrows, Roman temples, and Sutton Hoo to discoveries in Greece, on Crete, and of course, Egypt with the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, is accompanied by a look at a peculiarly British phenomenon—the folly. These are the architectural creation of the rich and the eccentric, odd throwbacks to ages past, ripe for the Keeper to have cultists put to some nefarious purpose. The section on ‘Britain in the Mythos’ sadly runs to just two pages, listing and mapping the locations for various works of Lovecraftian fiction and Call of Cthulhu scenarios. In addition, the Call of Cthulhu scholar will also spot the odd reference scattered throughout the book. Of course the ‘Britain in the Mythos’ section is up to date for 1987, but has long since been superseded. What it does highlight though is the lack of application of the Mythos to the British Isles in Green and Pleasant Land, it brings nothing new to the Mythos in Call of Cthulhu. No new cults or Mythos entities, or indeed a discussion of the Mythos in the United Kingdom. Typical of the time, but nevertheless disappointing.

Green and Pleasant Land contains three scenarios. The first of these is ‘The Horror of the Glen’ in which the investigators are hired by the famous ghost hunter, Harry Price, to investigate a brutal murder in the highlands of Scotland, said to be at the hands of a deadly ghost. It has everything for bucolically Celtic investigation—suspicious natives, a fire and brimstone priest, and a nicely detailed castle! There are some quite lengthy clues (sadly not replicated for ease of use), some of which are a little difficult to find, and a plot that echoes Lovecraft’s ‘Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family’. The climax of the scenario is rousing if linear, but this is a solid scenario that is a delightful period piece (I recently had the pleasure of playing it at UK Games Expo 2016). It is followed by ‘Death in the Post’, a less direct and less straightforward scenario that begins with the investigators being asked by an acquaintance to examine a strange piece of papyrus. They quickly learn that it is part of a mad sorcerer’s ongoing revenge and thwarting him will send them hither and thither around the country on his trail. It is a sprawling piece, much more difficult for the Keeper to run and potentially quite deadly that would probably make much use of the travel information provided earlier in the book. The challenge in running ‘Death in the Post’ is hampered by the lack of labels for the portraits of the various NPC victims. The third and last scenario concerns that most parochial of British pastimes—the canal holiday! ‘Shadows over Darkbank’ takes the investigators into the Black Country where a somewhat contrived request to investigate a canal tunnel collapse. Probably the most ambitious of the three scenarios in Green and Pleasant Land, this needs a careful read through if the Keeper is to grasp its plots and impart them successfully to his players. The choice of Mythos creatures in ‘Shadows over Darkbank’ is an oddity, effectively Deep Ones, but not Deep Ones, but then that could easily be changed.

It should be noted that the compendium, almost almanac-like structure of Green and Pleasant Land is due, like so many of Games Workshop’s Call of Cthulhu output, due to the origins of its sections as articles for White Dwarf. For example, the section on ‘Money & Prices’ was first seen in White Dwarf #70 as ‘Crawling Chaos: The Price is Right - Prices in 1920s Britain’; the ‘Characters’ section was originally seen in the White Dwarf #74 article, ‘Gentlemen and Players: A Guide to Creating British Investigators’; and then this fed back into the magazine with a section cut from Green and Pleasant Land. This was ‘Green and Pleasant Language: British Period Slang’, which appeared in White Dwarf #90 and is infamous for its discussion of the ‘Mummerset’ accent.

Physically, Green and Pleasant Land is a supplement of two halves. The background section uses a lot of period photographs and adverts—probably too many of the latter—whilst the second half, the scenarios, is renowned for its illustrations by Martin McKenna. These are superb pieces, often gothic grotesques that greatly impart the character of each of the NPCs. Unfortunately, because none of these portraits are labelled, it is often difficult to determine who is who for the scenarios.

Further, as a sourcebook for the United Kingdom, Green and Pleasant Land is far from complete. Now the book’s editor, Pete Tamlyn, states up front that he had material sufficient to fill two books of this volume’s size. Which begs the question, what was left out? What was definitely left out of Green and Pleasant Land is any discussion of the United Kingdom’s geography, of the differences in the peoples of its constituent parts, of any real options to play investigators of working class origins other than servants or sportsmen, and of any options to play female investigators. Part of the problem with all of these issues is that Green and Pleasant Land is very much an extension of Cthulhu by Gaslight, which published in 1986, gave more background and detail for the United Kingdom. Without access to that supplement and without being a student of history, the Keeper is going to do some researches of his own if he wants to run a game with any degree of historicity set in the United Kingdom of the period.

There is no doubt that Green and Pleasant Land is the best of the original books published by Games Workshop for Call of Cthulhu. By modern standards the background in the supplement feels somewhat light and akin to a series of bullet points than what would be wanted today. This is not to say that the information given is poor, but its lack does leave the Keeper with work to do. Perhaps the best of the new material in Green and Pleasant Land is the set of new Occupations which although too Pulp in tone, are really well done and a lot of fun. The three scenarios are solid if varied lot, none quite perfect, but none without a certain charm.

Overall, Green and Pleasant Land is an excellent supplement by the standards of the day, one that is held in a certain regard by those that recall it. The content is good and the scenarios are still playable these decades on…

—oOo—

As ridiculous as it was, I got to play ‘The Horror of the Glen’ on Saturday, June 4th at UK Games Expo as part of the Call of Cthulhu Masters. It was ridiculous because of the four players at the table, one knew the scenario and one had not only read it, but written a review of it (in other words, that was me). We all demurred and said that we were happy to play. It was good fun and we enjoyed it very much because the Keeper did a good job. Sadly it was announced that the Keeper in question, Sue Wilson, passed away recently. Sue was a fixture of UK conventions, big of cheer and big of presence, always happy and always friendly—she ran good games. I played in numerous scenarios she ran over the years and enjoyed them. There must have been so many players over the years that she ran scenarios for and I hope that she brought joy to her players each time. Sadly I did not know Sue away from the conventions, but it was never less than a pleasure to see her each time. I know that I will miss her at each and every one I attend.

No comments:

Post a Comment