—oOo—

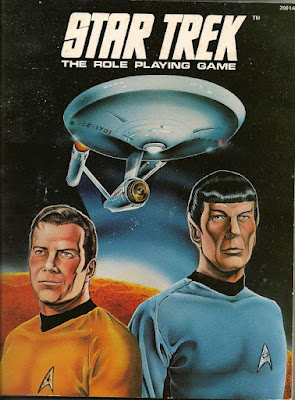

For many roleplayers, Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game would be their first Star Trek roleplaying game. Yet by the time of its publication in 1982 by the FASA Corporation, there had already been one roleplaying game published based upon the Star Trek franchise, Star Trek: Adventure Gaming in the Final Frontier, published by Heritage Models in 1978. It would soon be eclipsed by Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game and all but forgotten. Further, and despite its detractors criticising it for being too militaristic, Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game would set the blueprint for all Star Trek roleplaying games which would follow in its wake, even down to the latest, Star Trek Adventures, published by Modiphius Entertainment. Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game drew from a limited source of material rather than the wealth that we have today. Just the classic Star Trek series, Star Trek: The Animated Series, and the films, Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan. Later supplements would update the setting based upon the new films and eventually, Star Trek: The Next Generation, though with the latter not to Gene Roddenberry’s satisfaction and the licence would be revoked in 1989. In the meantime, the FASA Corporation supported the setting with numerous supplements and scenarios, including some well-received scenarios such as A Doomsday Like Any Other and Decision at Midnight. Further, with relatively little canon to draw from, Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game would famously provide content that would make its way into the depiction of various aspects of the setting onto the screen itself, mostly famously, The Klingons supplement by science fiction author John M. Ford (along with his Star Trek novel, The Final Reflection). However, much of this has been superseded by later development of the Star Trek franchise, including calculation of Stardates, the system of dates used in the series and Star Trek chronology. Yet to be fair, those differences really stem from the designers having to create content based on a limited source of material.

In Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game, players take the role of bridge officers aboard a starship belonging to Starfleet which serves the United Federation of Planets on missions which can involve deep space exploration, research, defence, peacekeeping, and diplomacy. This can be as members of the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise or even aboard their own vessel as their own characters. For the former, stats are included stats for Captain James T. Kirk, Commander Spock, Doctor Leonard McCoy, Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott, Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu, Lieutenant Uhura, Ensign Pavel Chekov, Nurse Christine Chapel, and others. For the latter, players could create Human, Andorian, Tellarite or Vulcan characters as per the classic Star Trek series as well as Catian and Edoan characters from Star Trek: The Animated Series. The Game Master had rules for creating NPC threats and characters such as Klingons and Romulans, whilst later supplements and scenarios explored the possibility of playing members of those two races. Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game included starship combat, world creation, advice for episode creation, and more.

Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game consists of three books—the forty-page Cadet’s Orientation Sourcebook, the forty-page Star Fleet Officer’s Manual, and the forty-eight-page Game Operations Manual. The Cadet’s Orientation Sourcebook is the background and setting book. It includes a timeline of Star Trek history, glossary of Star Trek terminology (everything from antimatter and beaming up to the UFP—United Federation of Planets—and Warp Speed), descriptions of the various starfaring races, Starfleet Command, encounters in space and what protocols to follow, equipment and weapons, shipboard facilities and systems, stats for the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise, plus those for Khan Noonian Singh, Harcourt Fenton Mudd, Sarek, Kor, Koloth, and Cyrano Jones, and ‘The Story of Lee Sterling’, a fictionalisation of the sample character created in the Star Fleet Officer’s Manual. It references various sections in that book, and whilst the sample Player Character’s sheet is given at the start of the book, the fiction does feel slightly out of place here. Other than what is possibly the longest backstory created for any sample Player Character, the Cadet’s Orientation Sourcebook does a good job of introducing the setting and laying out expectations as to what and how a player will be roleplaying in the game. Of course, with a roleplaying game like Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game, there will be a lot of information and content here that will be familiar, both in 1982 and now, but it is a decent introduction and reference guide, including the type of operational teams a Player Character might find himself attached to, starting with the Landing Party and expanding to cover Exploration Teams, First Contact Teams, and Diplomatic Contact Parties. Starfleet is described in some detail with particular attention paid to rank and position, because although Starfleet is not a military organisation, its ships will fight if they have to and its structure is very hierarchical. This greatly affects the positions taken aboard ship by the Player Characters and thus play. The section on ‘Encounters in Space’ is particularly enlivened by commentary from Captain Kirk.

The Star Fleet Officer’s Manual is devoted to just two aspects of Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game. The first is character creation and the second tactical combat. Once past the explanation of what roleplaying is, character creation in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game turns out to be different. Its nearest antecedent was Traveller, in which a player created a skilled character with history of several years’ service in an organisation at the end of which he was older, wiser, and skilled, if that is, he was not infamously killed as part of the creation process. Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game, although of course, a character in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game could not die as part of the process. This was not the only difference though. Where a player creating a character in Traveller could not necessarily know where his character would end up and what he could do, in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game the player did know. It was always as a member of the bridge crew aboard a starship, and in effect, a Player Character in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was always created to fill a role or position rather than being rolled randomly to see what the character would be like.

A Player Character in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game has seven attributes—Strength, Endurance, Intellect, Dexterity, Charisma, Luck, and Psionic Potential—which are expressed as percentile values. He has a Race, either Andorian, Catian, Edoan, Human, Tellarite or Vulcan, which will modify the attributes and, in some cases, provide an extra ability, such as the Edoan’s third arm and leg and the Vulcan capacity for Psionics. Beyond that, the Player Character has several derived factors, plus a long set of skills, which are also percentile based. To create a character, a player selects a Race, rolls three ten-sided dice and adds forty to create all of the attributes apart from Luck and Psionic Potential, which are percentile rolls. A random number of points is distributed as bonuses across all of the attributes bar Luck and Psionic Potential. A player receives several background and personal skills before entering Starfleet Academy and studying three base curricula—core, space science, and officer training, before enrolling in a branch school. These are Communications/Damage Control, Engineering, Helm, Medical, Navigation, Science, and Security. Throughout, the Player Character takes advanced training and outside electives before going on a cadet cruise. Once graduated, the Player Character typically goes to Department Head School and if intended to be a captain or first officer, Command School as well. Depending on the intended position, as well as if it will be aboard a Constitution class starship the Player Character will undertake three, four, or more tours of duty. The process is slightly complex and does take a while.

Name: Osetil Thoran

Race: Andorian Age: 34

Rank: Lieutenant Commander

Branch: Science

Cadet Cruise (Exploration Command, Constitution Class) Passed (Honours)

Tour 1: Colonial Operations Command (OER: 03/Outstanding), Two Years

Tour 2: Military Operations Command (OER: 24/Excellent), One Year

Tour 3: Galaxy Exploration Operations Command (OER: 13/Excellent), Four Years

Strength 85 Endurance 89 Dexterity 60 Intellect 70 Luck 73 Charisma 70 Psionic Potential 33

Max Op End 89 Inact Save 20 Unc Threshold 5 Wound Healing Rule 4 Fatigue Healing Rate 8

AP 10 To-Hit, Modern 40 To-Hit, Hand-to-Hand (Unarmed) 44 Bare-Hand Damage 2D10 To-Hit, Hand-to-Hand (Armed) 55

Administration 58, Carousing 34, Computer Operation 74, Computer Technology 10, Damage Control Procedures 10, Electronics Technology 10, Environmental Suit Operation 30, Instruction 10, General Medicine (First Aid) 10, Language (Klingonaase) 15, Language (Romulan) 20, Leadership 39, Life Sciences (Ecology) 10, Life Sciences (Exbiology) 10, Life Sciences (Zoology) 13, Markmanship, Modern Weapon 20, Negotiation/Diplomacy 19, Personal Combat, Armed 51, Personal Combat, Unarmed 29, Personal Weapons Technology 05, Physical Science (Computer Science) 37, Physical Science (Physics) 41, Planetary Sciences (Geology) 30, Planetary Sciences (Meteorology) 49, Planetary Survival (Arctic) 19, Small Equipment System Operation 19, Social Science (Federation Culture/History) 15, Social Science (Federation Law) 15, Space Sciences (Astrogation) 10, Space Sciences (Astronomy) 79, Space Sciences (Astrophysics) 82, Starship Sensors 74, Streetwise 20, Transport Operation Procedures 10, Zero-G Operations 10

Mechanically, Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game is at its most basic, a fairly simple system. When a player wants his character to undertake an action, he rolls percentile dice and attempts to roll equal to or under the value of the appropriate attribute, skill, or other value. It is simple as that, though the Game Master can apply modifiers depending upon the difficulty. The second half of the Star Fleet Officer’s Manual is dedicated to tactical combat. This uses an Action Point economy intended to be played out on a grid map with characters expending Action Points to move, use equipment and weapons, and engage in hand-to-hand combat. Firing weapons takes into account firing arcs, grazes, and more with energy weapons inflicting set level of damage and archaic and melee weapon damage being rolled. Most energy weapons are deadly. Disintegrate effects do exactly that, whilst most energy weapons will inflict enough damage to knock a character out. Thus combat in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game is deadly and to be avoided unless hand-to-hand combat. The glossary of terms at the back of Star Fleet Officer’s Manual is very useful.

The third book is the Game Operations Manual and it is the longest in Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game. This is for the Game Master and provides advice and tools for her to run the roleplaying game. There is good advice here on designing encounters and adventure scenarios, identifying the differences between linear and free-form or more open scenarios, but also suggesting how the best of both can combined and built towards a campaign. The nature of Star Trek adventures are also discussed, including planetside adventures, strange new worlds, new civilisations, and so on. These are supported with rules for creating the classic Class M world suitable for settlement by Humanity and populating it with alien species and even alien civilisations, covering its technological index, socio-political index, and more. These table provide the bare bones upon which the Game Master can flesh out the civilisation and make it interesting enough to set a plot there. There are rules for quick NPC design too, starting with members of Starfleet, but also including Klingons, Romulans, Orions, Gorn, and Tholians. The section is rounded out with specific advice on running scenarios, with particular attention paid to using play aids and in a nod to the tactical play of combat, the use of miniatures.

Over a third of the Game Operations Manual is dedicated to judging different aspects of the roleplaying game—game set-up in terms of ship, ranks, position, character creation, ground action, skill use, tactical combat, and both weapons and equipment use. There is a degree of repetition between the character creation tables in Star Fleet Officer’s Manual and the Game Operations Manual, which by today’s standards feels redundant and there is the aspect of the book commentating on a process for the player with things for the Game Master’s eyes only. This was how it was done when Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was published and there is new content alongside the old, such as the attribute modifiers for Klingons, Romulans, and other races. It is only at the end of the Game Operations Manual that starship combat is covered in any detail. Three options are covered, all three of which are role-based, with the Player Characters acting according to their role aboard ship—the Captain giving orders, the Science Officer scanning the enemy, the Chief Engineer assign power, the Helmsman manuevering the ship, the Navigator tracking potential targets and operating the Deflector Shields, and the Communications Officer attempting to thwart enemy jamming attempts and handling damage control. Initially, in the first edition of Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game the basics of what would become the Star Trek: Starship Tactical Combat Simulator was provided with the roleplaying game. By the second edition of Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game this was being suggested as the Star Trek III Combat Simulator, alongside Enemy Contact: Bridge Alert and “Using Your Imagination”. This is a quick and dirty system and not at all tactical, whereas both the Star Trek III Combat Simulator and Enemy Contact: Bridge Alert were, but available separately. With the “Using Your Imagination” option, the Game Master will need to create enemy ship details herself and judge the outcome of starship combat with some care. It is a pity that this could not have been fleshed out instead of the advice for Game Master on various aspects of the rules, as arguably, the “Using Your Imagination” option needed that advice, if not more development. Nevertheless, the concept of roleplaying what would otherwise be a tactical element in game play was new and innovative.

The other major differences between the first edition and second edition of Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game were the inclusion of details of various starship types, deckplans for both the U.S.S. Enterprise and a Klingon D-7 battle cruiser and a trilogy of scenarios. Of these three, the biggest omission from the second edition—and the version published by Games Workshop—in 1985 were the three scenarios. These are ‘Ghosts of Conscience’, ‘Again Troublesome Tribbles’, and ‘In the Presence of my Enemies’. In ‘Ghosts of Conscience’, the Player Characters’ ship is sent on a secret mission to locate the U.S.S. Hood. The crew find her on the edge of an astronomical anomaly and when a landing party beams aboard, it discovers that the Hood is heavily damaged and her crew dead after suffering horrendous violence. Inspired by the episode, ‘The Tholian Web’ this is a classic crew versus crew type story and makes a great deal of use of the U.S.S. Enterprise deckplans as the U.S.S. Hood is also a Constitution class starship. It is accompanied by some designer notes which add an interesting commentary to the scenario. In ‘Again Troublesome Tribbles’, the Player Characters are ordered to a research station and organise its shutdown, but the process is hampered by the presence of merchant and con-man, Cycrno Jones, Tribbles, and the arrival of a Klingon battle cruiser. Like ‘Again Troublesome Tribbles’, ‘In the Presence of my Enemies’ takes place in the Organian Treaty Zone and involves Klingons. The Player Characters are assigned to a diplomatic courier to ferry a Federation ambassador to negotiate a treaty with the government of the Lorealyn system which has access to intriguing new mineral resources. However, the Klingons have other ideas and attack and kidnap both crew and ambassador! This is the toughest of the three adventures, mostly taking place aboard a Klingon D-7 battle cruiser and thus making use of the Klingon D-7deckplans as much as the earlier ‘Ghosts of Conscience’ made use of the U.S.S. Enterprise deckplans. Overall, these are three solid adventures, clearly inspired by the original series, though of course ‘Again Troublesome Tribbles’ is either going to be a lot of fun or make the players groan!

Physically, Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game cleanly and tidily presented and looks decently laid out for its time. It is noticeably illustrated with black and white stills from the original Star Trek series. Some are crisply presented, others less so. The look of the book is by no means exciting. In fact, it all feels very technical in places and even a bit dull.

—oOo—

Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was reviewed by William Barton not once, but twice in the pages of Space Gamer. First in Space Gamer Number 64 (July/August 1983) in a lengthy, featured review, in which he concluded, “I like this game. And I think you will, too, despite any picky points you can find that don't quite agree with your own concept of how a Star Trek game should be (does it really matter that that there are no rules for wide-beam phaser stun?). It has its flaws as does any system and it wasn’t possible to cover every aspect of Star Trek in one game. But everything you really need for a satisfying Star Trek role-playing system is to be found here – in fact, just about everything you need for any SFRPG. So I recommend you not be put off by the high price of this package. Incidentally, FASA will release the rulebook, for $10, as a stand-alone item. Give Star Trek – The Role-Playing Game a try. I think you’ll be glad you entered the Final Frontier. This game, so far, is my pick of the best role-playing system of 1983. (Mission completed. Beam me aboard Scotty…)” (Note the original cost of Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game at the time of its original publication was $25—about $75 by 2023 prices.)

The second time that William Barton reviewed Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was in Space Gamer # 71 (Nov/Dec 1984), this time the second edition of the roleplaying game. He commented, “Overall, though, second edition Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game is an even better avenue to gaming the final frontier than its predecessor. Those who own the original won’t need this edition to continue to play, as both are compatible, but will certainly find enough new material that they won’t be sorry for buying it, If you haven’t tried ST:RPG – especially if new to SF roleplaying – I recommend this game over its competitors for ease of play, consistency, and sheer enjoyment.”

No less than Sandy Petersen reviewed Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game in the ‘Game Reviews’ department of Different Worlds Issue 30 (September 1983). He concluded with a personal note that, “Star Trek is the first science fiction game I have ever wanted to play in the strength of the game itself. I have played many science-fiction role-playing games simply because I love the genre, and hoped the game would serve as a tool to allow me to enjoy science fiction. But Star Trek was an end in itself. The game has the limitations and virtues of the series, which was followed slavishly. The game is certainly high-priced, but there is a fair amount of material in the game box. If you are one of those inventive game players that likes to take parts out of various different systems, using the best from each, there will be little to cannibalize from Star Trek. The systems are simple and derivative. But the game is worthwhile, at least for fans of the show.”

Steve List reviewed Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game in Ares Number 16 (Winter 1983). He wrote, “STAR TREK game is an ambitious game, generally well-done, with some minor flaws. The worst of these is in any case a matter of taste – the episodic nature of things versus the continuous campaign approach. Further, there is no reason a GM could not make her own campaign a continuous one if she should desire. The matter of a galaxy map is discussed in the rules, and the possibility is held out that one might be published in time. Beyond that, there is nothing really significant that not be cured by the supplements planned for release in the near future. Acquiring all the STAR TREK game material may be financially costly over time, but that is true of all major roleplaying games, What is provided in this package is well worth the price.”

Russel Clarke awarded Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game an overall score of nine out of ten in ‘Open Box’ in White Dwarf No. 58 (October 1984) and simply stated that, “Star Trek the RPG is a worthy addition to the SF role-playing genre and I highly recommend it.”

Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was reviewed by Steve Nutt in Imagine No. 22 (January 1985). He said, “The game places great emphasis on role-playing. If your group is hack and slash then they had better change their approach before they play Star Trek. After all, if you are Captain Kirk then you should act like him. The referee should also play the game in the spirit of Star Trek, with scenarios as wacky as you like. If the role-playing game is played like the film, then it is first class; if not, it could get rather bloodthirsty. It has to be pitched right.”

Star Trek: The Role-Playing Game was accorded a retrospective review by Phil Clare in Arcane magazine (January 1997). He described it as “Extremely successful when it was first released, this epic film license made for a great roleplaying game.”, before continuing with, “The game worked for a number of reasons. At the time the RPG hobby was still in its ‘hack and slay’ phase - mainstream science fiction RPGs were a little thin on the ground, and many players adapted the few that were available for use with a Star Trek background. It encouraged roleplaying rather than a ‘zap and slay’ style, which always resulted in a very short game anyway because combat was always terminal, and came with an enormous amount of support material including the usual adventure modules, sourcebooks, recognition manuals, deck plans and playing aids, the strangest of which was a Tricorder/Starship Sensors Interactive Display. Finally, it did have the words ‘Star Trek’ on the box which meant it was always going to sell in large numbers.” However, his conclusion was interesting given that Star Trek roleplaying games would quickly follow, including highly regarded versions from Last Unicorn Games and Decipher, Inc. “Despite FASA finally losing the license, it does seem rather odd that there isn’t a Star Trek RPG currently available despite interest in the past from TSR, Mayfair and Steve Jackson Games. Ironically, however, this is probably for the best because the Star Trek franchise is now highly formulaic, and let’s not forget the creative differences FASA had not only with Paramount, but also the original design team. All this should make those of you who own a copy not only particularly smug, but also secure in the knowledge that the likelihood of another ST:RPG of the same quality appearing is pretty slim. And any game designers reading should take this as a challenge.”

—oOo—

By modern standards, Star Trek: The Roleplaying Game looks plain, if not actually austere. Similarly, there is an austerity to the game system which veers from the tactical with the Action Point system and its wargaming style of play to the decidedly untactical, even narratively-focused play of the “Using Your Imagination” option for starship combat. Yet the trio of authors’ obvious love for Star Trek constantly shines through, whether that is in the advice for the Game Master or the three scenarios printed in the first edition of the roleplaying game. The rules for character creation undeniably fit the setting, even if they are clunky and the process is lengthy by modern standards, and the end result does feel as if the character has been to Starfleet Academy and served several tours. And despite that clunkiness, the rules for character generation are innovative as they create characters designed to fill roles aboard a starship and thus within the game, the process being to set to a standard or objective rather than simply to see what the result might be. Similarly, the starship combat rules are equally as innovative—whichever version is being used—as they encourage the Player Characters to work together and fulfil their roles aboard ship in a time of crisis. This all encouraged the players to roleplay members of Starfleet in the future of Star Trek, as did the combat rules—deadly when it came to its modern weapons, but more knockabout when it came to fist fights! It also encouraged the use of the Negotiation/Diplomacy skill and the various scientific and technical skills to solve problems and overcome hurdles rather the simple use of brute force. These design innovations have been replicated again and again in subsequent Star Trek roleplaying games, inspired of course, by the source material, but indisputably, Star Trek: The Roleplaying Game was there first. This is why Star Trek: The Roleplaying Game was the first great Star Trek roleplaying game and why it is so fondly remembered today.

I just dug out my copy recently. Way back in the day I don't think we knew how to run a game where the party wasn't a group of relative equals, compared to a starship's chain of command. Over the years I got my head around that part. Today it's the idea that anyone could have a disintigrator beam in the palm of their hands that makes me ponder adventure design. I need to grab some of the old FASA adventures.

ReplyDeleteI am still in awe of FASA's ability to make a coherent timeline out of the Star Trek universe.

It was, however, NOT the first RPG ever done of Star Trek. That honor (such as it is) belongs to Horizon Models.

ReplyDeleteIf you read the review, you may actually note that there is a link to a review of the very first Star Trek roleplaying game that I wrote in 2022.

Delete