It is the year 2007 and the Sinaloa Cartel, the largest drug trafficking organization in the world, operates a vast network of narcos, halcones, y sicarias whose sole purpose is to ensure the flow of drugs north across the border into Los Estados Unidos and the flow of dollars into the cartel’s coffers. Mexico is a narcostate in which the influence and corruption of the cartels has reached deep into every level of society, backed up by both bloody violence and corruption. One stop on that path is the Free and Sovereign State of Durango in northwest Mexico and it is here that the Sinaloa Cartel runs into primary enemy—Los Zetas. This rival cartel is renowned for its even greater, more obvious acts of cruelty than the Sinaloa Cartel to the point where both ordinary Mexicans and members of Sinaloa Cartel fear the Los Zetas, which mostly consists of ex-army special forces soldiers. The Sinaloa Cartel has few other enemies. Most of la Policía and los federales—the local police and the Mexican federal police—are in the pockets of one cartel or another, as are local businessmen and both local and national politicians. At the local level, that of a territory or plaza, the biggest dangers come from rival cartels, upstart gangs, and ambitious members of the cartel who more control of the drug trade in the area. Within the plaza, el narco wants everything to run smoothly and everyone to know he is in charge, el halcón wants to both protect the interests of his boss and have a greater involvement in it, el concinero wants to cook the drugs in safety, la esposa wants to protect her family even as it is in volved in the drug trade, la polizeta takes el narco’s money to protect his own life even as he giving information to los federales, la rata wants out of the cartel and has plenty of information to spill if she can last long enough, and la sicaria has been brought back to protect the interests of el narco and the plaza, but whose side is he on? All are desperate, all have made bad decisions and will likely suffer the consequences, and all will do their utmost to survive as their secrets and ambitions collide in Cartel: Mexican Narcofiction Powered by the Apocalypse.

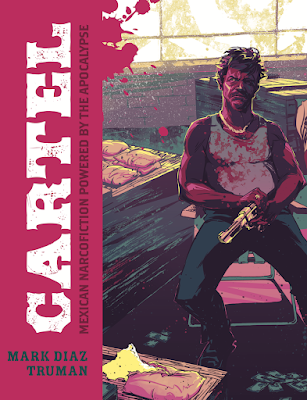

Cartel: Mexican Narcofiction Powered by the Apocalypse is a decidedly mature and darkly themed roleplaying game published by Magpie Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign. Inspired by the television series Breaking Bad and The Wire and the films, El Mariachi and Siccario, this roleplaying game draws heavily on the stories about the manufacture and trafficking of narcotics—cocaine, crystal meth, and heroin—in Mexico and north across the border into the USA. The players take on the roles of archetypes or Playbooks, each of which is involved with the Sinaloa Cartel and has one or more connections with each other. A combination of these connections, the characters’ agendas, their obligations to the cartel, and the cartel’s agenda serves to drive the drama of the roleplaying game, establishing tensions and hooks that will drive the story in a playthrough of Cartel. Which with all of that criminality, money, power, and obligation on the line, means that Cartel has potential for some great roleplaying.

Cartel is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’. What this means is that it uses the mechanics first seen in Apocalypse World, the 2010 roleplaying game which won the 2010 Indie RPG Award and 2011 Golden Geek RPG of the year and is from the designer of Dogs in the Vineyard. The core of these mechanics is a roll of two six-sided dice, with results of ten or more counting as a complete success or ‘strong hit’, results of between seven and nine as a partial success, a ‘weak hit’ or a success with consequences, and and results of six or less counting as a failure with consequences—or ‘no, but’. The dice are rolled against actions or ‘Moves’. For example, ‘Get the Truth’. When ten or more is rolled for this Move, the player using the Move gains a ‘strong hit’ and picks two out of three option. The options are that the target of the Move cannot mislead with the truth, confuse with falsehoods, or stonewall with silence. If seven, eight, or nine are rolled, the player has achieved a ‘weak hit’ and can only select one of the three options. The character making this Move also loses a point of Stress, reflecting a lowering of tension as the target of the Move is forced to be honest. When the Move is rolled, the player adds the appropriate stat, which typically ranges in value between -2 and +2. The four stats in Cartel are Face (social influence), Grit (tenacity and good fortune), Hustle (fast talk and persuasion), and Savagery (violence and reading others).

For example, El Coninero, Yolanda, has problem—the shipments she is sending out are arriving short, so she wants to ask El Halcón, Pepe, if he knows anything about this. Having cornered Pepe, Yolanda says to him, “Hey, Pepe, my last shipment came up short. This isn’t the first time. What do know about it?” The Master of Ceremonies says that this is a ‘Get the Truth’ Move. Yolanda’s player has to roll the dice and add her Hustle, which is +1. Her player rolls six, but the +1 makes it a seven. This is not a complete success, but it is a hit and Yolanda does get to reduce her Stress (well, she is going to get some of the truth after all). The options are that Pepe cannot mislead Yolanda with the truth, confuse her with falsehoods, or stonewall her with silence. If Yolanda’s player had rolled ten or more, her player could have selected two of these options, but can only choose one because of the roll. Yolanda’s player opts for Pepe not confusing her with falsehoods, which means that Pepe cannot lie. He responds with, “Look Yolanda, it was me, okay? I’ve been selling it on the streets. I had too though… there’s some dumbass cop taking a bigger cut of my pandillo’s money. He’s not one of ours, so…”

Cartel has ten basic Moves, which every Player Character has access to. These include ‘Justify Your Behaviour’, ‘Propose a Deal’, ‘Push Your Luck’, ‘Turn to Violence’, and more. Two other types of Move are conditional. Stress Moves such as ‘Verbally Abuse or Shame Someone’, ‘Lose Yourself in a Substance’, or ‘Confess Your Sins to a Priest’ are triggered when a character is in danger of suffering too much Stress. Heat Moves are triggered when a Player Character wants to avoid the notice of, or entanglement with, la Policía or los federales. These are ‘Avoid Suspicion’, ‘Leave a Messy Crime Scene’, and ‘Flee from Los Federales’. The basic Moves are detailed in a two-page spread each, while the others are given just the one page each. Half of each description is given over to detailed and engaging examples of play.

Further, players have access to Moves known only to their characters. These Moves, what a character knows or can do, are defined by their archetype or Playbook. Cartel itself has seven Playbooks. These are ‘El Concinero’, who cooks or manufactures the drugs; ‘La Esposa’, the spouse entangled in the lies of their partner; ‘El Halcón’, the ambitious young gang member; ‘El Narco’, the local boss in charge of an area or la plaza; ‘La Polizeta’, the cop corrupted by the cartel as much as he is trying to bring it down; ‘La Rata’ is the compromised mole in the cartel who wants out, but the only way is through the cartel; and ‘La Sicaria’, the cartel veteran enforcer or killer who has managed to survive thus far. The Moves in each Playbook are unique and thematically appropriate to the archetype. For example, the ‘Amante’ Move for ‘La Rata’ is made when the Player Character shares an intimate night with a lover, the player rolls and adds the character’s Face stat. On a strong hit, the Player Character can ask two questions of her lover, but only one on a weak hit. A hit also clear the Player Character’s Stress. On a miss, the Player Character reveals something about themself and so places themselves in danger.

Besides Moves, each Playbook has Extras and Llaves—or Keys. Extras represent a Playbook’s connections or resources, essentially their support. So, El Concinero has a lab where the drugs are cooked, La Esposa a family and obligations, El Halcón his loyal Pandilla or gang, El Narco a Plaza through which drugs are moved and sold, La Polizeta connections to an anti-cartel taskforce, La Rata his wretchedness at his situation, and La Sicaria his weapons and gear, which represent how they conduct his tasks. Each Key or Llave represents a means of a character gaining Experience Points. Thus, El Concinero has Secrets, Debt, and Arrogance. The first grants him Experience Points when he lies to someone close to him about his illicit activities; the second when he takes on a new loan or has to ‘strain your finances’ to meet family needs; and the third, when he uses his superior knowledge or experience to verbally shame or abuse someone they care about. Earned Experience Points are spent on Advances which range from improved Stats and support options to new Moves and resolving support issues. All seven Playbooks are highly detailed, including a guide on playing each Playbook, notes on each of the Playbook’s Moves, as well as a list of inspirations for the Playbook.

Character creation in Cartel is in part a collaborative process. Each player selects a Playbook and together work through the options it gives, deciding on a name, look, and gear as well as adjusting a Stat and deciding on Moves, Llaves, and connections or resources. Each player also establishes ‘Los Enlaces’ or links with other characters, ideally other the player characters, but NPCs are acceptable too. Guiding the players through this process is the Master of Ceremonies—as the Game Master is known in ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ Games—who will be asking questions and helping to build the relationships and backgrounds to each of the Player Characters.

In play, this is the primary role of the Master of Ceremonies, to ask questions, push and prompt the players, and build their characters’ involvement in the setting. For this she has the Moves of her own, such as ‘Inflict stress’, ‘Escalate a situation to violence’, and ‘Lean on a secret’, but the most important one is more of a directive—to be always asking the Player Characters, “What do you do?”. The Master of Ceremonies’ Moves are not as extensively described as the others in the game, but they are not as complex. The advice for the Master of Ceremonies is extensive though, beginning with how to set up and frame scenes, and to keep them meaningful to the fiction. It also covers how to use and pace her own Moves, examining each Playbook, managing the player versus player interaction and conflict at the heart of Cartel, using NPCs, and how to set up, run, and end the first session. It is supported by a lengthy, six-page example of play.

Damage in Cartel is managed as either Stress or Harm. The first represents mental damage, whilst the second is physical damage. Both are greatly deleterious to a character’s wellbeing. Interestingly, whilst the outcome of the ‘Turn to Violence’ Move will inflict Harm on the intended victim, it also inflicts Stress on the person doing it. Should a character suffer from too much Stress or Harm, then a player can clear by undertaking certain related Moves. For example, ‘Verbally Abuse or Shame’ or ‘Lose Yourself in a Substance’ as Stress Moves and ‘When You Get Fucking Shot’ as a Harm Move. Most damage-related Moves inflict Stress though and when a character suffers enough Stress, a Stress Move is obligatory. Stress Moves invariably have negative consequences as much as they relieve a character of Stress and further add to the drama of the game.

In terms of background, Cartel offers details of the city of Durango in Mexico, located between Mexico City and the US border, near the Pacific coast. This is part of the Sinaloa Cartel’s territory, although there are rival cartels working the area. It is here that the Player Characters are supplying, working, operating, and protecting a plaza, essentially a personal territory they are responsible for. Both the cartels and the law are covered as well as a broad history of both Mexico and the Drug War, the major players in the Drug War, and the culture which has developed as a result of the Drug War. The city of Durango is described, though in more of an overview than any great detail, and here the Master of Ceremonies may want to conduct some research or gather some photographs of the city to help her players visualise where their characters are living and working.

Physically, Cartel: Mexican Narcofiction Powered by the Apocalypse is a very well-presented book. It is clean and tidy with a large typeface and excellent artwork throughout, often in the calavera or ‘Catrina’ style. One standout feature of the writing is the number of examples of play, typically two for many of the Moves. These clearly explain how each Move works and highlights not just how the game is played, but also how the Moves work the tensions in the game and thus its incredible storytelling potential.

However, as rich and as powerful as the storytelling possibilities are with Cartel, the roleplaying game has a number of problems. The most obvious of which is the subject matter, the players are creating and roleplaying characters involved in the drug trade and if not committing the acts of violence and savagery perpetrated by some members of the cartels, then very much connected to the cartels that do. This is different than merely reading about it in a work of fiction or watching it on television. The experience is not vicarious, but personal, often viscerally so. As much as Cartel does not glorify its subject matter or its protagonists, it demands a degree of involvement and complicity that some players will not want to engage in and that is understandable. Cartel is not a roleplaying game for them, but even those who are prepared to play a roleplaying game of this nature need to be aware of what they are playing and the maturity which that demands.

Another issue is that Cartel is specifically written with Mexico and the Latino experience in mind, and that may well be alien to some of the game’s audience. Especially outside of North America. Even the writing here is an issue given that although primarily written in English, there are a lot of Spanish phrases and Mexican colloquialisms used throughout (which in some cases turn out to be terms of abuse), and as much as this adds to the flavour and feel of the book, it can come across as slightly mystifying. A more expansive glossary might have helped, even if that meant publishing bad language in the book. Being able to portray the world of the cartels on the streets of Durango with any degree of verisimilitude, let alone accuracy—and to be fair Cartel is aiming to create the feel of the former rather than the latter—demands a lot of the player and his skill as a roleplayer.

Cartel: Mexican Narcofiction Powered by the Apocalypse is an incredible piece of design which brings to life the greed, desperation, and drives of men and women living and working in a narcostate that pushes them to make poor choices and suffer the consequences. It makes great demands of both players and the Master of Ceremonies, asking them to commit to telling tough stories, have their characters carry out terrible deeds, and pay for them. If not in their deaths, then emotionally. By any standards, Cartel: Mexican Narcofiction Powered by the Apocalypse is about roleplaying in a horrible situation with no clear paths to absolution or redemption, but that situation and its Player Characters—through their Playbooks—encourage, even demand, great roleplaying and powerful storytelling.

No comments:

Post a Comment