Sunday, 26 August 2012

Beware Parties Bearing...

Saturday, 18 August 2012

Dave Gorman versus Boardom

Ultimately, the point behind Dave Gorman vs. The Rest Of The World is that there is no point to it, at least in comparison to other Dave Gorman projects. Can he find enough people named Dave Gorman in “Are You Dave Gorman?”? Will he find enough Googlewhacks in “Dave Gorman's Googlewhack Adventure”? Or rather that there is no drive to it, no sense of urgency. It is as meandering as the author’s journey up and down the country, a lazy if pleasant travelogue of a read that matches the holiday that the author took in getting to play the games described in the book. That is, until the book’s penultimate game, the playing of which takes an unnerving and unsettling swerve… This swerve though, is the book’s counterpoint to its actual point. That playing games as an adult can be as fun as when you were kid, that it is as fun as any other social activity.

Friday, 17 August 2012

Once in No-Man's Land

|

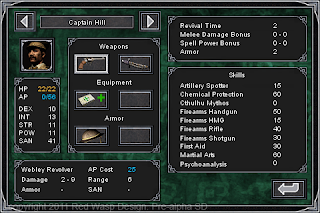

| A Sample Character: Captain Hill |

|

| The redoubtable Sid Brown alerts Captain Hill as to the imminent danger! |

Good Georgians Aghast

Saturday, 11 August 2012

Wizards Go Euro

As the owners of the great Avalon Hill brand, it is no surprise that the board games published by Wizards of the Coast to date have fallen into the “Ameritrash” category. To label them as such is not denigrate them, for their emphasis has been highly developed themes, characters, heroes, or factions with individually defined abilities, combined with player-to-player conflict and a high level of luck. The publisher’s latest title has proved to be anything but an “Ameritrash” board game, but is instead a classic style “Eurogame,” which means relatively simple rules, a short playing time, a degree of abstraction rather than simulation, player interaction, player competition rather than player combat, and attractive physical components. What is more, this is a game based on Dungeons & Dragons, and specifically on the Forgotten Realms setting. Its title is Lords of Waterdeep.

Most Dungeons & Dragons deal with the themes inherent in those two words – “dungeons” and “dragons.” So they focus on delving into dungeons, facing dragons, and so on. Not so, Lords of Waterdeep. It is set in Waterdeep, the City of Splendors, the most resplendent jewel in the Forgotten Realms and a den of political intrigue and shady back-alley dealings where powerful, but masked lords vie for control of the city through of the region’s organisations that include the City Guard, the Harpers, the Knights of the Shield, the Red Sashes, and the Silverstars. They send out their Agents to acquire Buildings and access to better resources; gain Gold to make the many purchases necessary to ensure their rise to power; the means to Intrigue with their fellow Lords; and hire Adventurers whom they can send out on missions or Quests that once completed with spread their influence and gain them true power.

Designed for play by between two and five participants, aged twelve and over, once learned, Lords of Waterdeep can be played in an hour, no matter what the number of players. The box contains a game board, a rule book, five player mats, one hundred Adventurer cubes, one-hundred-and-twenty-one Intrigue, Quest, and Role cards, thirty-three wooden pieces that include the game’s various Agents and the score markers, and one-hundred-and-seventy card tokens that include the Building tiles and Building control markers, and plenty of Gold. All of which fits easily and neatly into the game’s insert tray that holds all of the game’s components almost perfectly.

Lords of Waterdeep’s game board measures 20” by 26” and depicts the city port of Waterdeep in Faerûn. Besides the Victory Point track around its edge and the spaces for the Intrigue and Quest cards, most of board has spaces for various Buildings that include Aurora’s Realms Shop, Castle Waterdeep, and Waterdeep Harbour as well as empty spaces where the players can put up Buildings of their own. Each of the Buildings provides a specific benefit. For example, the Aurora’s Realms Shop gives four Gold; the Builder’s Hall lets a player purchase an Advanced Building and bring it into play; Waterdeep Harbour allows a player to use an Intrigue card; the open-air stadium that is the Field of Triumph is where you can hire Fighters; new Quests are available to take at Cliffwatch Inn; and taking control of Castle Waterdeep lets you go first on the next round and draw an Intrigue card.

Besides the nine Basic Buildings marked on the board, Lords of Waterdeep includes twenty-four Advanced Buildings. These work in a similar fashion to the Basic Buildings, but the benefits provided by each are usually better. For example, when a player visits the Smuggler’s Dock, he can spend two Gold in order to hire four Adventurers, although only Clerics and Fighters; The Waymoot accumulates Victory Points that any player can visit and collect; and when at The Palace of Waterdeep, a player can direct the Ambassador at the beginning of the next round – and the Ambassador always acts before anyone else can take their turn. A side benefit to owning an Advanced Building is that when another player uses it, the owner gains a small benefit. For example, when another player uses the Smuggler’s Dock, its owner receives two Gold, and with The Waymoot or The Palace of Waterdeep, he receives two Victory Points. (This does not happen when a player uses his own building).

Like the game board, the twenty-four page rulebook is done in full colour. It is well written, with quite a lot of information that includes plenty of examples. There is also a reasonable amount of background information too; enough that fans of the Forgotten Realms will appreciate the references, but not enough to overwhelm the casual player who does not roleplay, or who does not play Dungeons & Dragons. Overall, the rule book requires a careful read, but the rules themselves are fairly easy to grasp.

There is a player mat colour coded to each of the game’s five organisations – the City Guard, the Harpers, the Knights of the Shield, the Red Sashes, and the Silverstars. Each mat has spaces for his Agent Pool and other resources, plus his Completed Quests, as well as indications around the side to place his Active Quests, Completed Plot Quests, and his Lord of Waterdeep card.

The game’s one-hundred Adventurer cubes are divided into four colours – white, orange, black, and purple – representing Clerics, Fighters, Rogues, and Wizards respectively. These are the game’s primary resources, which along with Gold, are what a player will need to complete Quests.

At the heart of Lords of Waterdeep, and what the players are trying to complete, are its Quests, represented by the Quest cards. There are sixty of these and they come in five types – Arcane, Commerce, Piety, Subterfuge, and Warfare. Each Quest card gives the requirements necessary to complete and the rewards it grants when completed. For example, the “Domesticate Owlbears” Arcana Quest card requires one white and two purple – or one Cleric and two Wizard cubes, and rewards the completing player with eight Victory Points, one Fighter or orange cube, and two Gold. A second type of Quest card is the Plot Quest card, which when completed gives an extra reward throughout the rest of the game. For example, the Skulduggery “Install a Spy in Castle Waterdeep Castle” Plot Quest card requires four Rogue or black cubes and four Gold to complete, and when done do so, not only rewards a player with eight Victory Points, but for every subsequent Skulduggery Quest completed, rewards him with another two Victory Points.

The cards that the players will use throughout the game are the Intrigue cards. These tend to grant a player extra Adventurers or extra Gold, or penalise rival players. For example, the “Spread the Wealth” Intrigue card gives both its player four Gold and another player of choice, two Gold; whilst the “Assassination” Intrigue card forces every other player to discard a Rogue or black cube from his tavern on his player mat. If a player cannot discard a Rogue, he must pay two Gold to the player who put the Intrigue card into play. Another type of Intrigue card is the Mandatory Quest which when given to another player forces him to complete that Quest before any of the others before him. For example, the “Stamp Out Cultists” Mandatory Quest Intrigue card forces a Lord to expend a Cleric, a Fighter, and a Rogue cube to complete it before moving onto his other Quests. Sadly, he only receives two Victory Points for completing it.

The first card though, that each player will receive is a Lord of Waterdeep card. Each one of these depicts one of the members of the secret council that governs the city, along with their name, some flavour text, and an effect that in providing a benefit at the end of the game will influence a player’s actions during the game. For example, Nymara Scheiron gives a player an extra four Victory Points at the end of the game for each Commerce and Skulduggery Quest completed, whereas Larissa Neathal gives six Victory Points for each Advanced Building she controls at the end of the game.

At the start of the game, each player receives a player mat, the Building control markers, and Agents, all of the same colour. The number of Agents received varies according to the number of players. With fewer players, each player receives more Agents; with more players, they receive less. This is the game’s core balancing mechanic. However many Agents a player starts with, every player receives a further Agent at the start of the second half of the game. Each player receives two Quest cards, two Intrigue cards, and a single Lord of Waterdeep card. This last card is kept hidden until the end of the game when everyone works out their final score. Lastly each player receives some Gold, the amount varying according to play order. The player who goes receives just four Gold, the next five, then six, and so on until the fifth player – if there is one – receives eight Gold. This is the game’s second balancing mechanic.

The game is played over the course eight Rounds. In each Round, the players take it in turn to assign a single Agent and then if they can, complete a Quest. Each Agent is assigned to a space on the board in an available Building or Advanced Building space. When he does, the Agent gives the player the benefit from that Building. Most Buildings have a single space, so that once an Agent has been assigned there, no Agent can be sent there to make use of its benefit, though some Intrigue cards allow a player to assign an Agent to an already occupied building. Thus if a player wants to purchase and construct an Advanced Building, he must assign an Agent to the “Builder’s Hall” before anyone else, or wait until the next Round. In which case, he probably wants to assign an Agent to Castle Waterdeep gain the opportunity to go first at the start of the next Round. Otherwise, a player must assign an Agent to another Building.

Two Buildings – Cliffwatch Inn and Waterdeep Harbour – have multiple spaces, so that more than one Agent can be assigned there, even by the same player. The former is the source for new Quest cards, while the latter allows a player to use an Intrigue card. Once an Agent is assigned, if a player has sufficient Adventurers, and sometimes Gold, to complete the requirements given on a Quest card, he can complete it and score Victory Points for doing so.

Lastly, and after all of the Agents have been assigned, any player with an Agent assigned to Waterdeep Harbour can reassign that Agent to any remaining unoccupied Building. This rewards the player for his cunning in sending an Agent to Waterdeep Harbour and playing an Intrigue card. The Round is over, everyone receives their Agents back, and a new Round begins until all eight have been played. At game’s end everyone counts up the Victory Points gained form completed Quest cards, plus unassigned Adventurers and unspent Gold, and the person with the most is the winner.

Lords of Waterdeep plays at reasonable pace, once the rules have been grasped, and offers a decent amount of game play and replay given how simple the rules really are and how light the game is. This is helped by the variety available in the Quest and Intrigue cards, but mostly in the Advanced Building cards. With twenty-four available, it is unlikely that all of them will come into play. The game also scales well, playing as well with two players as with five.

In terms of game play, Lords of Waterdeep rewards careful planning. Each player needs to be looking at what he needs to complete the Quests that he has in front of him. Of course, he also needs to get to the Buildings that he wants, but with rivals competing for the same space, this is not possible, so a player should also try and get the best out the available Buildings that he can. This can be alleviated if a player goes first, but in general, the closer a player is to going first the better. There is also some advantage in purchasing and constructing the Advanced Buildings as they provide more spaces where an Agent can be assigned. Further, if another player uses one, then the owning player also gains a small, but sometimes important benefit.

All of the Buildings in Lords of Waterdeep can play an important role during the game, but three tend to be more favoured than the others. They are the Builder’s Hall, because it allows Advanced Buildings to be purchased and constructed; Waterdeep Harbour, not just because an Intrigue card can be played, but also because an Agent assigned there can be reassigned; and lastly, Castle Waterdeep as it grants a player an Intrigue card and means that he can go first in the next Round.

Agents though, are in short supply, even after the extra one is gained at the start of the game’s second half. This means that the players must assign them with care so as not to waste their action.

Physically, Lords of Waterdeep is very nicely put together. All of the playing pieces have been done in wood and the rest of the pieces in sturdy card, though the Intrigue, Quest, and Lord of Waterdeep cards have been done slightly too thin a cardstock. The rulebook itself is bright and attractive and easy to read. For an American game, the look and feel of Lords of Waterdeep is anything but that. It has the look and feel of a Eurogame.

In terms of theme, the grimy fantasy of the Waterdeep of the Forgotten Realms does not feel pasted on, a common complaint with this type of game. This is not to say that the mechanics behind the rules of Lords of Waterdeep could not be taken and have a new theme applied to them. It would take some effort, but in the meantime, the Dungeons & Dragons theme is applied with great care, and it is a theme that avoids many of Dungeons & Dragons’ clichés, primarily because it removes the concept of going on adventures and down dungeons. This is done by placing the players in the role of hiring the adventuring parties rather than being part of them – as in so many other games.

What is telling about Lords of Waterdeep is that Wizards of the Coast describe the format of this game as being “Non-traditional.” This is an odd claim for the publisher to make. Lords of Waterdeep is not a Non-traditional game. It is more or less, a traditional Eurogame, with worker placement and resource management mechanics similar to those found in well-known Eurogames such as Agricola, Caylus, and Puerto Rico, amongst many others. All games and mechanics that the designers at Wizards of the Coast and in particular, the designers of Lords of Waterdeep will be familiar with to some degree. The only way in which Lords of Waterdeep is Non-traditional is that it is not a classic American or Ameritrash design, and to describe it as “Non-traditional” is to belittle both this design and Eurogames in general. Certainly, it shows a wilfil ignorance upon the part of the publisher.

Although its various bits and pieces and possibly the business of the rulebook make Lords of Waterdeep look more intimidating than it really is, Lords is really a medium to light Eurogame that is just a step on or two up from introductory games such as Settlers of Catan or Ticket to Ride. Certainly, it is much lighter and less complex than similar games such as Caylus and Agricola. Similarly, the game’s Dungeons & Dragons theme might be off-putting, but it never imposes itself on the game or its players. What is pleasing about the game is that the designers have achieved a balance between the theme and the mechanics that will attract both Eurogame players and players of Dungeons & Dragons players, but whilst both will be attracted to the game, Lords of Waterdeep is still more Eurogame than a Dungeons & Dragons game. Above all, Lords of Waterdeep is an enjoyable, decently themed Eurogame that uses familiar – almost traditional – mechanics to good effect.

Tuesday, 7 August 2012

The Gloom that overcame Glaaki

Back in 2004, Atlas Games published a card game of a singularly ingenious, yet depressingly design. It told the story of how the members of four families were driven each to a mournful end after a life time of ill omens, distressing events, and ennui to end it all. The cleverness of the design lay in the nature of the cards, for they were not cards at all, but each was a slice of thin, transparent plastic marked with various icons, images, and pieces of text. Game revolved laying cards upon the top of various family members, the transparency of the cards enabling various elements of the cards underneath the uppermost one to remain visible and in play until such times as they were covered up, their effects negated and replaced with the uppermost icons. In addition, the design of the game and its theme, inspired by the art and stories of the artist, Edward Gorey, enabled the game to work as a story telling game too, letting the players narrate how each member of his family was driven first to despair, and then to his or her death… The game in question was Gloom – The Game of Inauspicious Incidents & Grave Consequences, and it would win its publisher, and its designer, Keith Baker, the 2005 Origins Award for Traditional Card Game of the Year.

In 2011, Keith Baker returned to Gloom. Not though to provide us with another expansion, but rather to explore a new theme using the same basic format and mechanics. That new theme draws from a source as uncaring as that of the original Gloom before going on to exacerbate it with elements that are in turn batrachian, inhuman, and tentacular, if not to say, wholly unwholesome. The theme in question is the works of H.P. Lovecraft, and the new game is Cthulhu Gloom -- The Game of Unspeakable Incidents and Squamous Consequences.

As with the original Gloom, the aim in Cthulhu Gloom is to drive your “family” down a path of horror and madness to an untimely death, suffering the most horrifying stories possible, all the whilst attempting to keep the members of your opponents' family happy, healthy, and annoyingly alive. This done by playing Modifier cards and Event cards on top of the Character cards, the aim being to drive each character’s Pathos as deeply into the negative so as to give the lowest Self-Worth score possible before doing them in by having them suffer an Untimely Death. A game comes to an end when an entire family has been eliminated, all of its members having fallen prey to the same inevitable inter-dimensional doom that will befall us all – though the fate of the family members in Cthulhu Gloom will at least be more entertaining. In a non-Euclidean sense, that is... At which point the Pathos inflicted upon the dead members in each family is totalled, along with any points gained from Story Cards played. The player whose family has the lowest Family Value – or the highest negative Family Value – derived from the Self-Worth scores of those Family members who met an Untimely Death wins the game.

More recently, the original Gloom has been the subject of an episode of Wil Wheaton’s Tabletop. It is worth watching to get an idea of how the original Gloom is played and thus an idea of how Cthulhu Gloom is also played.

One difference between Gloom and Cthulhu Gloom is the nature of its families. In Gloom, the members are for the most part, related by blood. In Cthulhu Gloom, this is not necessarily the case. So whereas the Whateleys are all related as members of the old Dunwich family, and the Marshes are all related as members of the old Innsmouth family, the members of the other two families in Cthulhu Gloom are not. They are instead members of the faculty or students at Miskatonic University or staff and patients at Arkham Sanatorium. Thus, they are a family by association.

Designed for two to five players, aged thirteen years and up, Cthulhu Gloom is intended to play in an hour. The game comes with twenty Character cards, fifty-four Modifier cards, eleven Event cards, twenty Untimely Death cards, and five Story cards, along with the double-sided rules-sheet. Of all the cards, the Character cards, each of which has the name of the character, an illustration of the Character, and a piece of flavour text on it, do not have any game effect icons or text on them. The Modifier cards all also illustrated, but have one, two, or three icons on the left-hand and right-hand side of the illustration, place a game effect described in the text below. The icons on the left are always Pathos Points, the values ranging from +25 down to -30; whilst the icons on the right are either Effect icons, which indicate how and when the game effect takes place, or Story Telling icons – Blank, Goblet, Horror, Investigation, Madness, Magic, or Romance – which have two uses in the game. When a Character has certain icons visible on him, it allows other cards that require those icons to be visible to be played on him. The other use is if the game is being played as a Storytelling Game, in which case the icons are used to help tell the story of how the Character came to his Untimely Death.

For example, the “Gibbered with Ghouls” Modifier card has an illustration of a Ghoul on it, and to the illustration’s left is a single “-10” Pathos Points icon, whilst to the illustration’s right, is a Persistent effects icon (meaning that the card’s effect continues until covered with that of another card), plus a Madness and a Horror icon. The game text below tells the player that whilst his draw limit is decreased by 1 card, he can now draw from the top of the discard pile as well as the draw pile!

Event cards lack the illustrations and icons of the other card types, and once played from your hand, are discarded. For example, “The Thing on the Doorstep” allows a player to move one Untimely Death card from a dead Character to another along as the soon-to-be dead Character has negative Pathos Points, or “The Voorish Sign” which can be used to cancel another Event card when it is played.

Story cards also lack icons, but they do have dramatic and powerful effects when played and can benefit a player’s Family Value at the end of the game. For example, “The Call of Cthulhu” requires a player to have two Madness icons visible, but at the end of the game, all of the Pathos Points for a player’s Characters count towards his total Family Value, whether they are alive or dead! This is a very powerful card!

Lastly, the Untimely Death cards, one for each of the Family members in Cthulhu Gloom, are all illustrated with a skull. Some also have Pathos Point icons or blank icons that cover up Storytelling icons, but all have a small piece of game text that can be positive or negative. For example, the “Wasted Away” Untimely Death card adds an extra -10 Pathos Points if the Character it is played on has a Madness icon visible. Once an Untimely Death card is played on a Character, he and his cards are set aside. He is out of the game until the end, although he can be affected by certain Event cards.

At the start of the game, each player receives his Family, or four of them in a four-player game to prevent the game from going on too long, the discarded Family members combining to form a fifth Family if there is a fifth player; and a hand of five cards. Two random Story cards are placed in the middle of the table.

On his turn, a player can take two actions. He can play a Modifier card on any Character still alive – this will alter the Character’s Pathos Points and Storytelling icons, and give an effect too; play an Event card for a one-time effect; play an Untimely Death card on any character with negative Self-Worth score; claim a Story card and its benefits, though it is only possible to have one of these; discard his hand, or pass. These actions can be done in any order except that an Untimely Death card can only be played as a first action. A player cannot place a really good Modifier card on one of his Characters to make his Self-Worth score even worse and then protect the newly depressed Character by playing an Untimely Death card. He must wait until his next go to play the Untimely Death card as his first action, giving every other player the opportunity to improve that Character’s Self-Worth score and so make the playing of the Untimely Death card less attractive.

Strategy in Cthulhu Gloom is simple. Decrease your Self-Worth of the characters in your Family whilst attempting to improve that of characters in rival Families. In other words, make them have a less miserable time than yourself! A player should not refrain from having a rival Character suffer an Untimely Death, especially if his Self-Worth is not very low. This effectively takes that Character out of the game and prevents his Self-Worth from being lowered even further.

In addition to keeping a careful watch of the Self-Worth of each of the Characters in his rival Families, a player should keep an eye on the icons and the text visible on their cards. By covering these up with the icons and text on other Modifier cards, a player can stop negate the effect of a good card or reduce the number of Storytelling icons in play and so prevent an effect from a Story card, for example.

As clever a design as Cthulhu Gloom is, and Cthulhu Gloom is a clever design, it suffers from the same issues as Gloom did. The cards are too small. Not too small for a player to read them when they are in his hand or in front of him on the table, but too small to be read by other players sat round the table. Which leads to a lot of peering at other players’ Families and the cards played on them, and this has a disruptive effect as from a distance the cards appear to be a little too busy. In some ways, this fussiness seems strangely appropriate, but it is almost as if the game would have been better if the cards had been double the size… Of course, the cost would have been as proportionately large as well.

Physically, the cards in Cthulhu Gloom are well done, and pleasingly illustrated by Todd Remick. If there is a physical issue with the cards it is that in places it appears that the Storytelling icons do not match. This had me looking for a “quarter Moon” icon until I realised that it was actually a simplified Madness icon. The rulebook requires a care read through though, as the game actually looks more complex than it is.

Although not mechanically any different from the original Gloom, this is a well done reiteration. Where it improves on the original game is its theme, as thematically, Cthulhu Gloom is highly entertaining, especially if you know your Lovecraftian fiction. The game takes a slightly “tentacle in cheek” approach to its source, one that is just humorous enough to entertain, but not so as to detract from awfulness that will be inflicted upon the Families. Cthulhu Gloom is a fiendishly luminescent design with a fussiness that complements the theme and the source. Mannered and maddening, Cthulhu Gloom -- The Game of Unspeakable Incidents and Squamous Consequences is satisfyingly sanity sapping.

Saturday, 4 August 2012

Four for One: a Campaign

Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré is designed for beginning characters who are members of the King’s Musketeers. Whilst working for Lieutenant Jean-Marc de Guerre, the player character Musketeers will find themselves sent on missions that will take them back and forth across France, from the heart of Paris and France’s borders with the Spanish Netherlands during a Habsburg invasion to her coasts in the fogbound North West and then the disgruntled South West. There is room in the campaign for slightly experienced characters, but it is really intended for use as a starting campaign. There is also room between the four parts of the campaign that takes place over the course of a year or so, for a GM to add his own adventures so that the campaign’s story can be extended and leavened out.

As the campaign’s title, Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré suggests, the plot behind the campaign revolves around a dishonoured King’s Musketeer. He is not known to the characters, although he is connected to one of them, and his search for revenge will draw them into his plans.

Subtitled “Revenge is a dish best served cold!”, Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré opens with “Désir Mortel.” The player characters are assigned the task of investigating the deaths of Sergeant Roger Dupin, Paul de Chamest, and de Chamest’s manservant near the village of Champs-Saint-Denis. Seigneur Dupin had offered to sponsor de Chamest , a young noble from Champagne for induction into the King’s Musketeers. The scenario, a mix of investigation, combat, and interaction, feels quite traditional in terms of storytelling, coming with it as it does with more victims, obstructive authorities, and a certain sense of misdirection. That said, the adventure contains lots of period detail and plenty of room swashbuckling action. One nice touch is that the adventure opens with a set of opening scenes that are tailored to the player characters’ Flaws. So for example, a character with the Flaw of Lustful can play through an opening scene that finds him awakening in the bed of his latest conquest only to find that her husband is home early! These are lovely inclusions and not only help to get the scenario and the campaign off to a colourful start, they also give each player a chance to shine.

The plot underpinning the campaign gets underway properly with the second scenario, “Le Baiser de la Mort.” As the Habsburg invasion of North East France continues, the player characters are once again tasked to investigate the death of a former musketeer, this time one Francois Joubert. Joubert had been tasked with delivering payment to a mysterious agent, Le Faucon. It is known that payment was made, but no information was forthcoming from Le Faucon, and now Joubert is dead. The trail takes the characters to mysterious and fabled island of Mont Saint-Michel, the waters around it increasingly fog bound, the monks that serve at its famous abbey, acting increasingly oddly, and Cardinal Richelieu’s having taken an interest in the Musketeers’ mission. This is a much more complex affair with a lot more going on, with multiple plot lines and numerous antagonists. That said, the setting itself nicely corrals them and keeps everything from sprawling out of control.

By the end of “Le Baiser de la Mort,” the player characters should be aware that a mysterious man known as “Delmar” is plotting against both them and the King’s Musketeers. Not only is this “Delmar” someone that is known to those who once dealt with the same outré threats to the King and to France that the player characters deal with now, but he also happens to be an ex-Musketeer! As “Rançon de Sang,” the third part of the campaign opens, the player characters will be able to gain further information about their antagonist from a very famous ex-Musketeer as well as an inmate of the Bastille. Visiting what is perhaps the most famous prison in France proves to be disturbingly genteel, although it does bring the characters to the attention of Cardinal Richelieu, again… Further information comes from an old contact that not only is another of “Delmar’s” ex-colleagues still alive, but also that his daughter, Jeannette d’Aronde, has been kidnapped! Duty-bound to rescue her, the player characters must travel to Bordeaux where all evidence points to a famous pirate as being the kidnapper!

Given the intrigue of the first two parts of Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré, “Le Baiser de la Mort” initially feels a little slow with little to punctuate its opening series of roleplaying encounters. Fortunately, once the player characters are out of Paris and reach Bordeaux events pick up a pace with plenty of opportunity to swashbuckle!

The campaign comes to a close and a finale with “Le Mousquetaire Final.” With no more leads as to the whereabouts of “Delmar,” the player characters are initially caught up with preparations for war with the Habsburgs, but their attention is fully piqued when Delmar first strikes from afar using magic and then forces them to act when he kidnaps their superior, Lieutenant Jean-Marie de Guerre. Of course, he is laying a trap for them, but what choice do the player characters have? Worse the trail forces the characters to confront the worst excesses of a French army on the march and leads them into the notorious Gévaudan region…

Physically, Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré is well written and well presented. It could do with an edit here and there, and is a bit lacking in certain places. The fact that the book contains black and white art instead of the colour art of the PDFs is understandable, but it would have been nice if the NPCs had been illustrated and some maps had been included. Neither is wholly necessary to run the campaign though. In terms of writing, the conclusions to each scenario and to the campaign itself feel underwritten and abbreviated, but with a little roleplaying upon the part of the GM should get around this.

There is nothing to stop a GM from running one part of Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré after another, but the campaign works better the more adventures that a GM runs between its parts. The adventures themselves present an excellent mix of intrigue and interaction, action and adventure, swordsplay and swashbuckling, making Le Mousquetaire Déshonoré an excellent way to get your All For One: Régime Diabolique campaign off to an entertaining start.