On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another Dungeon Master and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support. Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will be compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry.

Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is a little different. Penned by Zedeck Siew—author of Lorn Song of the Bachelor—and drawn by Munkao, it is the fifth title published by the A Thousand Thousand Islands imprint, a Southeast Asian-themed fantasy visual world-building project, one which aims to draw from regional folklore and history to create a fantasy world truly rooted in the region’s myths, rather than a set of rules simply reskinned with a fantasy culture. The result of the project to date is eight fanzines, plus appendices, each slightly different, and each focusing on discrete settings which might be in the same world, but are just easily be separate places in separate worlds. What sets the series apart is the aesthetic sparseness of its combination of art and text. The latter describes the place, its peoples and personalities, its places, and its strangeness with a very simple economy of words. Which is paired with the utterly delightful artwork which captures the strangeness and exoticism of the particular setting and brings it alive. Barring a table of three (or more) for determining random aspects that the Player Characters might encounter each entry in the series is systemless, meaning that each can be using any manner of roleplaying games and systems, whether that is fantasy or Science Fiction, the Old School Renaissance or not.

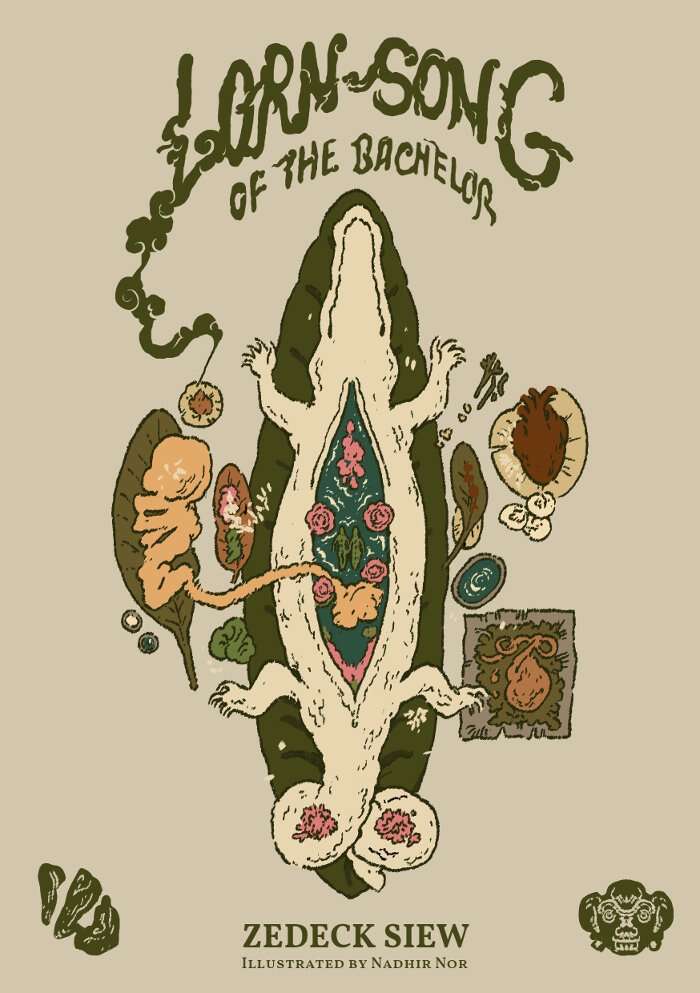

The first, MR-KR-GR The Death-Rolled Kingdom, described the Death-Rolled Kingdom, built on the remains of great drowned city, now ruled by crocodiles in lazy, benign fashion, they police the river, and their decrees outlaw the exploration of the ruins of MR-KR-GR, and they sometimes hire adventurers. The second, Kraching, explored the life of a quiet, sleepy village alongside a great forest, dominated by cats of all sizes and known for its beautiful carvings of the wood taken from the forest. The third, Upper Heleng: The Forest Beloved by Time, takes the reader into a forest where its husband Time moves differently and the gods dictate the seasons, Leeches stalk you and steal from you that which you hold dear, and squirrels appear to chatter and gossip—if you listen. Andjang: The Queen on Dog Mountain, the fourth, explores a vampire kingdom desperate for trade.

Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is another island, lost at the tail of an archipelago. Ironically it is known as Lodestone, for it cannot be found or reached by conventional means of navigation—a ship has to set sail in a random direction and get lost. Which does not always work… Yet many have reasons to go there, primarily to gain access to the skills and abilities of the magicians of the isle, which is said to be very great indeed. Such petitioners typically have a great need, for the price charged by the magicians is also great. The strangeness of Stray Virassa is primary presented through NPCs, first those who are travelling to the island, second through the magicians themselves, and lastly, through the citizens of the island’s port city, Ka-Lak-Kak—and this is done in two ways. First in random tables to generate NPCs and second sample ready to portray NPCs.

The great news is that is Upper Heleng: The Forest Beloved by Time, MR-KR-GR The Death-Rolled Kingdom, Kraching, Andjang: The Queen on Dog Mountain, Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell, and the others in the Thousand Thousand Isles setting are now available outside of Malaysia. Details can be found here.

So a traveller to Stray Virassa could be going there because they have been cursed by a business rival that whenever they speak, they cough up maggots. They do not seek a cure, but a reciprocal curse. Besides their strangely fouled mouth, they are known for the crooked wig which constantly slips from their sweat-slicked head, and whilst travelling light, their neck is heavy with brass amulets to ward off bad spirits. The magicians include Diffa Fu, an overly worldly twelve-year-old and fertility specialist who can put a baby in any women—or man, who also collects skulls and whose word is final for any descendant of such skulls she owns!

Ka-Lak-Kak itself is a ghost city and city of ghosts, solid during rainstorms, transparent under direct sunlight, which might lead to the disappearance of a floor several storeys high! It is the Fourteenth Hell, the Hell reserved for those lost at sea. None of these have feet, but simply fade away below the knee, so in life, one might have been a soldier who died fighting pirates and is armed with a crossbow with a string made of ectoplasm which fires bolts of flame, and as a ghost, has a hand whose fingers end in crab claws that they constantly click. Now, they herd the floating lanterns that replace ghosts too lazy to manifest and are philosophical about their new existence, except for a hatred of their husband, who constantly cheats on them. The irony of the soldier’s situation is that Ka-Lak-Kak and Stray Virassa is a pirate port. Not to traditional pirates, but ghost pirates whose raids are never planned and always unguided. When ghost pirates weigh anchor, their boat capsizes. Only to right itself somewhere on the water, be it a river canal or a mountain lake, to raid and reave before capsizing their vessel again and return home! If the wreck of a lost ship can be found—pirate or not, the nails which hold its thick planks together can be harvested and if used to construct another ship, will ensure that the new vessel never sinks—for no ship ever sinks twice.

Ka-Lak-Kak and thus Stray Virassa is also home to the largest settlement of Mu-folk, outside of ancient, lost Mu, including its last potentate, the indolent Xeng Xin, whose days are spent running spirit dens and taking his share of the island’s pirate raids when not in a haze of opium. He also occasionally still claims that Mu is rightfully his, though he has no word from the old country in some time. Perhaps a loyal lieutenant might employ someone to bring news and even an individual from the former kingdom? As with previous issues, accompanying Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is an insert, a foldout poster of extra tables. These include tables for determining the details of ghosts who have wandered the sea-floor for decades, and a drop table of ‘Memories of Mu’ to flesh out questions that the Player Characters might ask whilst on Stray Virassa.

Physically, Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is a slim booklet which possesses the lovely simplicity of the Thousand Thousand Isles, both in terms of the words and the art. The illustrations are exquisite and the writing delightfully succinct and easy to grasp.

As with entries in the Thousand Thousand Isles series, Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is easy to use once the Player Characters get there. There are hooks and plots which the Game Master could develop and engage the players and their characters with, and the setting is easy to adapt to the world of the Game Master’s choice, whether that is a domain on the Demiplane of Dread that is Ravenloft for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition or a remote kingdom in nautical setting such as Green Ronin Publishing’s Freeport: The City of Adventure or even a lost isle in H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands, whether for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition or another roleplaying game. However it is used, if the Game Master can get her Player Characters to its borders—and its randomly accessed nature makes that relatively easy—Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell is creepy and magical and weird, simply, but evocatively and beautifully presented and written pirate and ghost haven intentionally lost.

—oOo—

The great news is that is Upper Heleng: The Forest Beloved by Time, MR-KR-GR The Death-Rolled Kingdom, Kraching, Andjang: The Queen on Dog Mountain, Stray Virassa: The Lost and Fourteenth Hell, and the others in the Thousand Thousand Isles setting are now available outside of Malaysia. Details can be found here.