Lastly, ‘Places in the City’ describes various locations. These include ‘Harbold’s Raceway’, a crumbling arena where the city watch once trained, but is now a drinking and gambling den where races of all sorts are held, on all manner of beasts and mounts, including fan-favourite, Uudo Kuusk and his six-legged biomechanical undead creature built by Roland Repnik. At ‘Yesterday’s Lost Wares’, the wooden golems will push to make a deal over any and all of the goods on sale in this two-storey pawnshop, whilst ‘The Statue of the Defeated Dragon’, a piece of public art considered so wasteful that both the artist and the city official who commissioned were cornered and murdered, has become a meeting for thieves, though in certain light, the statue is so life-like that the unwary might believe it to be an actual red dragon!

Monday, 29 August 2022

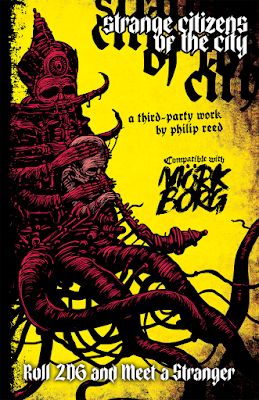

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] Strange Citizens of the City

Lastly, ‘Places in the City’ describes various locations. These include ‘Harbold’s Raceway’, a crumbling arena where the city watch once trained, but is now a drinking and gambling den where races of all sorts are held, on all manner of beasts and mounts, including fan-favourite, Uudo Kuusk and his six-legged biomechanical undead creature built by Roland Repnik. At ‘Yesterday’s Lost Wares’, the wooden golems will push to make a deal over any and all of the goods on sale in this two-storey pawnshop, whilst ‘The Statue of the Defeated Dragon’, a piece of public art considered so wasteful that both the artist and the city official who commissioned were cornered and murdered, has become a meeting for thieves, though in certain light, the statue is so life-like that the unwary might believe it to be an actual red dragon!

Sunday, 28 August 2022

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] One of Us #1

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] Planar Compass #2

Planar Compass #2 was published in November 2021. Following on from Planar Compass #1, it promises strange sights, ever changing environmental dangers, and monsters the likes of which the Player Characters will never seen. Opening with a quick table listing all of the planes and explaining that the contents of issue are designed for mid-level play, Fourth Level and higher, and what titles are required to use it contents. It notes that the waters of the Astral Realms are the thoughts, hopes and dreams, and nightmares of all sentient beings of the multiverse, physical matter alien to it and are always either an intrusion or a traveller. Such waters are endless and there are many places that a good crew with a solid ship will be able to sail far and away to strange places—if both survive the dangers of the Astral Plane, many of which are intrusions and breakthroughs from other planes.

Saturday, 27 August 2022

1982: The Warlock of Firetop Mountain

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

Today is ‘International Gamebook Day’, a celebration of interactive fiction. Which also means that in 2022, it is also Zagor’s birthday. Zagor of course, is the ‘Warlock of Firetop Mountain’ whose labyrinth will be explored by the reader of the eponymous game book, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. Written by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone and published by Puffin, it was the first of some fifty-nine entries in the Fighting Fantasy series which would encompass numerous genres—horror, Science Fiction, superheroes, and more—but would always, always come back to fantasy. The series would sell millions of copies, have its own magazines, and get its own history with YouAre The Hero: A History of Fighting Fantasy™ Gamebooks, and The Warlock of Firetop Mountain would receive sequels, be adapted into board games and computer games and a roleplaying scenario for Dungeons & Dragons, Third Edition and even an audio adventure.

There were of course, ‘choose your adventure path’ style books available before the Fighting Fantasy series began with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. There was the Tracker series published in seventies, plus the ‘Choose Your Adventure Path’ books and various solo scenarios for Tunnels & Trolls, the roleplaying game from Flying Buffalo, Inc. There were computer games, such as The Hobbit for the ZX Spectrum, also published in 1982. None of these had the advantages or the impact of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The ‘Choose Your Adventure Path’ books presented simple choices with nothing else for the reader to do to influence what happened from one paragraph to the next. The Tracker series—such as Mission to Planet L—had the advantage of using illustrations to present the reader with choices, but the stories were quite short. The solo adventures for Tunnels & Trolls required the reader to own and understand how to play Tunnels & Trolls before even attempting to play through them. Computer games such as The Hobbit required a player to own the computer and have ready access to a television, as well the knowledge to install the game. Then for both the Tunnels & Trolls solo scenarios and computer games like The Hobbit, they were not as readily available.

In comparison, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain required

nothing more than the ability to read, understand some simple rules, a pair of

six-sided dice—easily found in any board game, let alone a toy shop, and pencil

and paper. Even if the reader lacked dice, numbers were printed on the book’s

pages that he could flip through to generate the required numbers. With or

without dice, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain was easily portable. Plus it was

a book, which meant that the player was reading—usually a good thing as a far

as most parents were concerned. It was also a book which could be found on the

shelves of your local bookshop, meaning that its market presence and penetration

had the potential to be huge. So it proved. This only increased as sales rose,

again and again, so that Fighting Fantasy titles became bestsellers. Obviously

advertised in the pages of White Dwarf magazine, because Livingstone was the

editor, its sales reached out beyond those of the hobby, with many readers

being introduced to interactive fiction, roleplaying, and fantasy through their

reading and playing of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain and other Fighting Fantasy series titles.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain began by asking the reader

if he was brave to take on the monsters and magic of Firetop Mountain? The treasures

within lay ripe for the taking, but in order to do that the powerful warlock

Zagor must be slain! To face him, the mighty hero must navigate the tunnels and

caverns that form the maze of his mountain stronghold, often facing the warlock’s

horrid minions and monsters who would kill you as much as look at you. Even if

the hero can find his way through every twist and turn of Zagor’s maze, defeat

every monster and minion encountered, and even Zagor himself, he still must

have both keys to unlock the chest containing the warlock’s mightiest treasures!

Only then will he have survived the perils of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain!

There is little fanfare to the instruction of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. It very quickly into the explanation of what it is and what

the reader will need before getting to roll up his character, who has Skill,

Stamina, and Luck. Skill is primarily used in combat—added in opposed rolls

against the monsters, Stamina is the character’s life force and health, and

Luck covers everything else. Actually, Luck mostly covers running away,

although other instances of its use are explained in individual paragraphs.

Combat works by the player rolling for his character and adding his Skill and

then doing the same for the monsters. The highest result each round wins and

inflicts damage on the other. Anyone reduced to zero Stamina is dead. In comparison

to most monsters, the character does start play with a lot. In addition, the

reader’s character has a sword and leather armour and a potion, which will

restore one of his three stats.

Then onto page one and the labyrinthine cavern complex inside Firetop Mountain.

It is a brutal journey. Very quickly the reader encounters Goblins, some asleep,

some in a murderous mood, then Orcs, traps, a box with a snake which will try

and bite him, a ferryman to bargain to take him across the river into the

second part of the adventure. Besides sneaking past Goblins and killing Orcs, the

reader might find himself gambling with Dwarves, getting lost in a maze—the non-linear

nature of the book manages to make a maze even more annoying, distracting Ogres,

and much more. To be fair, there is very little story to The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, and arguably the character who the reader is controlling is morally

suspect given his attitude towards torture in one scene and the fact that he

wants to take Zagor’s treasure when the warlock is merely minding his own business

and not oppressing the nearby populace. That said, the story is one that the reader

is creating in reading and playing through The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. As

much as it is ‘dungeon bash’, the authors are really setting a template for the

other Fighting Fantasy titles to come which would be more sophisticated and

mature in their storytelling.

Of course, throughout The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, the

reader and his character is in constant peril and danger of dying. Combat is

not the only way that the reader can die in The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. This

increased sense of peril and the possibility of death is arguably the solo game

book’s innovation, making survival and its play uncertain. Whatever way in

which he does die, the reader has to start again, this time with new stats

rolled up for a new character. Where the new character will have an advantage

is in having access to a map showing the progress of the previous character or characters.

This is because the reader is encouraged to draw a map as he reads through and

explores the tunnels and caverns of Firetop Mountain. In this way he maps out

the routes explored and looks for untried ones, again and again each time his

character dies and he begins anew. Here then, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is working like a Rogue-style computer game in which death is permanent and the

player has to start again. Of course, the new character has the advantage of

the map and hopefully learning from previous wrong choices. It is notable that

in many cases that map would be replicated again and again as new players read

through the solo game book for the first time.

Physically, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain looks and feels

like a novel. It is not of course, but the standard of presentation is

excellent, with the artwork of Russ Nicholson—sadly lacking in later printings

of the book—really standing out and giving the book its signature look.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain was reviewed in White Dwarf No. 36 (December 1982) in Open Box by Nicholas J R Dougan. He opened with, “The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, is, in gaming terms, a fairly simple programmed dungeon. Its uniqueness, however, as a may be guessed for the publisher’s name and the its paperpack format, is that it is designed to sit on the children’s shelves of a bookshop as much as in a gaming shop.” Before awarding it ten out of ten, he concluded that, “The book would make an ideal present for anyone who has expressed an interest in role-playing games, or indeed any young brother (or sister!). I imagine that the minimum age would be about ten, but I would recommend it to novice and veteran players alike for quite a few hours of entertainment. I imagine that the minimum age would be about ten, but I would recommend it to novice and veteran players alike for a few hours of entertainment. The authors, Steve Jackson (UK not USA) and Ian Livingstone (there’s only one), are to be congratulated on the successful development of an original idea that should benefit the hobby.”

More recently, author and publisher, Chris Pramas, chose The Warlock of Firetop Mountain as his entry in Hobby Games: The 100 Best, published by Green Ronin Publishing in 2007, also the year of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain’s twenty-fifth anniversary. He described The Warlock of Firetop Mountain as, “…[A] pioneering release that popularized the solo gamebook and successfully brought the roleplaying game experience to a wider audience. This book alone sold over two million copies and it was only the first of the Fighting Fantasy series. The Warlock of Firetop Mountain spawned 58 more Fighting Fantasy books in the original series, a support magazine, a board game, an ambitious spinoff series, several computer games, two traditional roleplaying games, and a series of fantasy novels. Then there was the legion of imitators, another sure sign of success. Not bad for a slim paperback less than 200 pages long.”

—oOo—

The influence and reach of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is undeniable. Millions of copies sold, reprinted again and again, and adapted

to other formats, it started the Fighting Fantasy series and led to numerous

other publishers their own lines of game books too. Yet it also introduced many

readers to the concept of interactive fiction and many readers to the concepts

behind roleplaying as well, and for gamers, it gave them something to play away

from the game table and something that was very much game related that they

could buy at their local bookshop. This combination of accessibility and availability

helped increase the understanding of what roleplaying was and what its kind of

play was like in a way that computer roleplaying games would later do, and in

the process, it helped make both more acceptable.

For all of its influence and reach, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain remains still a nasty little dungeon, perhaps just a little grim and a

little perilous with a dash or two of humour, where there is the real chance of

the reader’s character dying at the hands of some monster or by some mishap. For

the teenager starved of gaming it enabled gaming again and again until the

cavern complex was fully explored and mapped out, and ultimately The Warlock of Firetop Mountain defeated and his treasure taken. Coming back to it as adult,

it feels familiar, evoking memories of the first few times it was played and of

the first few steps taken into all too many dungeon.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain did not invent the form of interactive fantasy fiction,

but it made it popular and made it accessible. It is also made it fun.

Happy International Gamebook Day 2022 and happy fortieth birthday Zagor!

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] Meanderings #2

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

The first of the action ‘Options’ in Meanderings #2 is ‘Off the Chart! Might Deeds Beyond the 7+ for Warriors & Dwarves’. This is a solution to problem of players always rolling high for their Dwarf and Warrior characters when it comes to their Mighty Deeds die, the results always topping out at seven and more, and so always feeling the same. What though if both Dwarf and Warrior could roll higher? The article increases the upper range the results from seven to fourteen plus and supports with expanded tables for blinding, disarming, pushback, and precision attacks, as well as rallying and defensive manoeuvres, and trips and throws. The result is to make both Classes more effective at higher Levels and more fun to play. A useful option and something which could easily appear in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Companion, were there such a thing.

‘Let the Dice do the Talking: A Narrative Skill System for the DCC RPG’ gives a way of introducing more narrative to the play of Dungeon Crawl Classics and its skills. Inspired by the author playing a game of Fantasy Flight Games’ Edge of the Empire, it has a player roll three dice any time that his character attempts a skill and have all three dice rolls count. The individual results range from ‘Misadventure’ (a roll of one), ‘Misstep’ (below Difficulty Check), ‘Success’ (above Difficulty Check), and ‘Coup’ (maximum result), but because three dice are being rolled, any roll could involve one, two, or three of these results and then the Judge has to interpret them narratively. This is not a simple matter of the Judge interpreting the result as a yes or no outcome. Instead, it requires the Judge to interpret a more granular outcome which can mix a ‘Misadventure’, a ‘Success’, and a ‘Coup’ in one or roll or a ‘Misstep’ and two ‘Success’ results, for example. Mechanically, it is a simple and quick means of gradating results in a less linear fashion, but in terms of implementation it requires both Judge and her players to adapt to interpreting the results in a non-binary fashion. Whilst it is narratively it is clearly intended to add some fun complications and outcomes to the game, it also adds complexity and slows down actual play, until both Judge and her players are more skilled with making the narrative calls on the dice results. Making this adjustment—and it very much is an adjustment—may be too big a step for some groups.

Friday, 26 August 2022

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] Night Soil #Zero

[Fanzine Focus XXIX] Crawl! Number 12: The Luck Issue

Published by Straycouches Press, Crawl! is one such fanzine dedicated to the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. Since Crawl! No. 1 was published in March, 2012 has not only provided ongoing support for the roleplaying game, but also been kept in print by Goodman Games. Now because of online printing sources like Lulu.com, it is no longer as difficult to keep fanzines from going out of print, so it is not that much of a surprise that issues of Crawl! remain in print. It is though, pleasing to see a publisher like Goodman Games support fan efforts like this fanzine by keeping them in print and selling them directly.

Where Crawl! No. 1 was something of a mixed bag, Crawl! #2 was a surprisingly focused, exploring the role of loot in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game and describing various pieces of treasure and items of equipment that the Player Characters might find and use. Similarly, Crawl! #3: The Magic Issue was just as focused, but the subject of its focus was magic rather than treasure. Unfortunately, the fact that a later printing of Crawl! No. 1 reprinted content from Crawl! #3 somewhat undermined the content and usefulness of Crawl! #3. Fortunately, Crawl! Issue Number Four was devoted to Yves Larochelle’s ‘The Tainted Forest Thorum’, a scenario for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game for characters of Fifth Level. Crawl! Issue V: Monsters continued the run of themed issues, focusing on monsters, but ultimately to not always impressive effect, whilst Crawl! No. 6: Classic Class Collection presented some interesting versions of classic Dungeons & Dragons-style Classes for Dungeon Crawl Classics, though not enough of them. Crawl! Issue No. 7: Tips! Tricks! Traps! was a bit of bit of a medley issue, addressing a number of different aspects of dungeoneering and fantasy roleplaying, whilst Crawl! No. 8: Firearms! did a fine job of giving rules for guns and exploring how to use in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game and Crawl! No. 9: The Arwich Grinder provided a complete classic Character Funnel in Lovecraftian mode. Crawl! Number 10: New Class Options! provided exactly what it said on the tin and provided new options for the Demi-Human Classes, whilst Crawl! Number 11: The Seafaring Issue took the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game.

She should be so lucky.

Monday, 22 August 2022

Miskatonic Monday #126: A Fishy Business

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

Author: Joerg Sterner

Setting: Jazz Age Maine

What You Get: Fifteen page, 15.25 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: Between the Mob and the Mythos in Maine.

Plot Support: Staging advice, three handouts, six NPCs, three Mythos monsters to be, and one Mythos artefact.

Pros

Cons